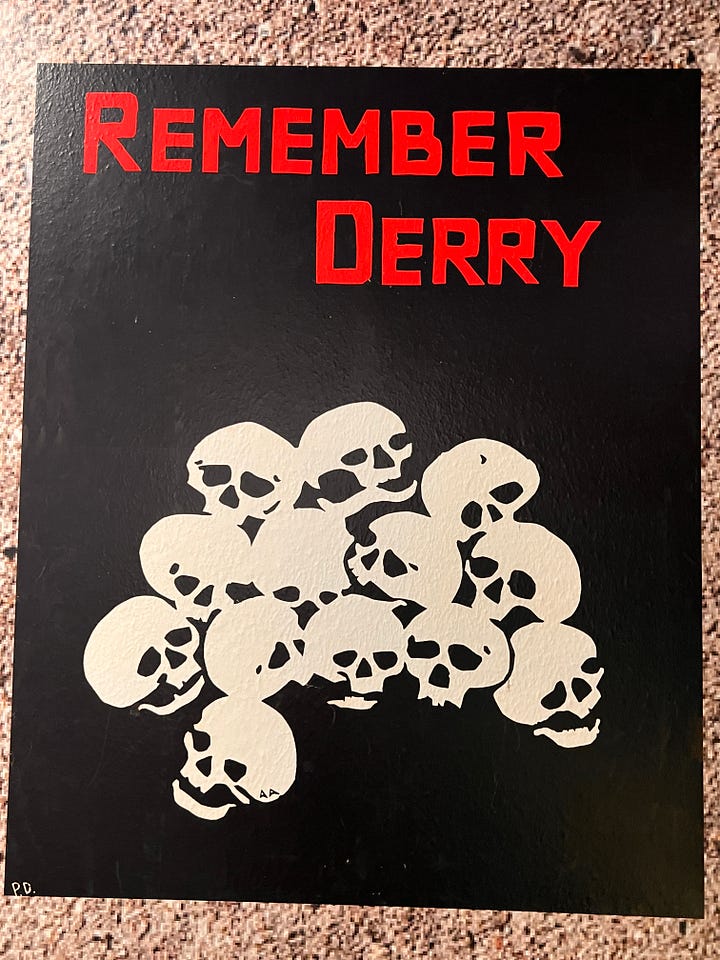

Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland

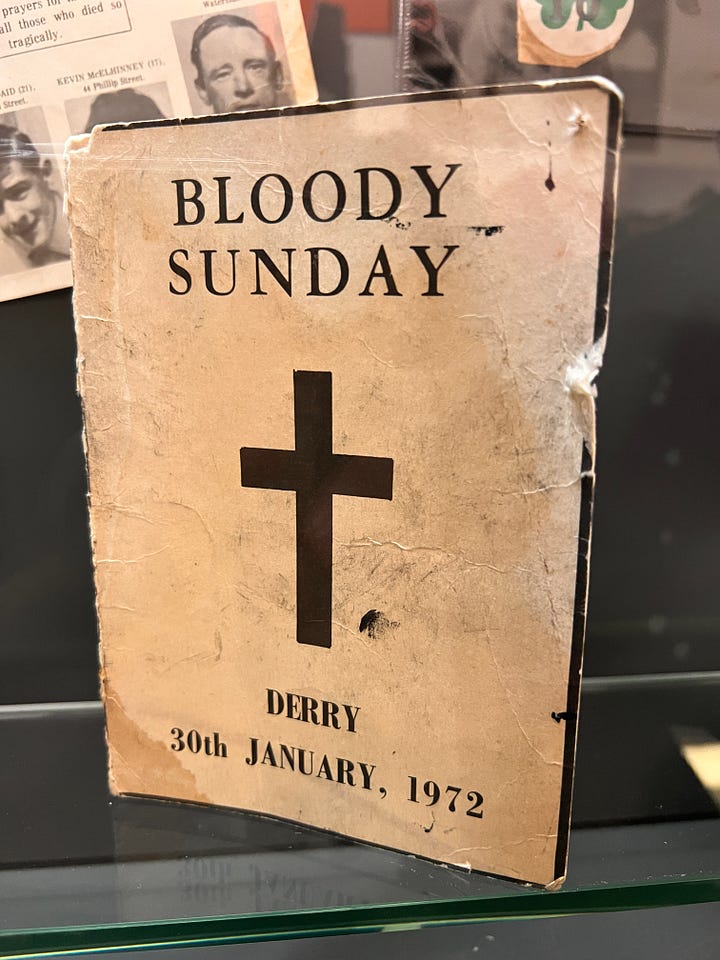

On January 30, 1972, a peaceful protest for civil rights turned violent and scarred a nation forever.

It only took about 10 minutes, but in that short period of time 13 people lay dead (a fourteenth man later died of his wounds) and more than a dozen others had been wounded.

What began as a peaceful protest march ended in a tragedy known as Bloody Sunday.

The murders took place in Derry (also known as Londonderry), Northern Ireland on January 30, 1972.

Background

“The Troubles” had already begun a few years earlier.

The Troubles is the term given to the decades of sectarian violence that wracked the small country of Northern Ireland from the late 1960s until the 1998 Good Friday Peace Agreement.

On one side were the nationalists comprised mainly of Catholics who wanted Northern Ireland to become part of the Republic of Ireland and free of British rule.

On the other side were the unionists made up mainly of Protestants who wanted to Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom.

Catholics in Northern Ireland and Derry, the nation’s second-largest city, faced discrimination such as a lack of political power due to gerrymandering and voter suppression as well as discrimination in employment and housing.

Catholics viewed the Protestants as supporting an oppressive imperial power. So, Catholics protested for self-determination and greater civil rights.

Their protests and clashes with British law enforcement forces led to The Troubles.

Even though nationalists were a majority in Derry, the unionists had the power of the police—the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)—and the British military behind them to ensure “law and order.”

While nonviolent organizations such as Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) attempted to press for change peacefully, other organizations such as the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) and the Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) believed that only armed conflict would bring about freedom from British rule.

There were also those among the Protestant unionist faction that believed violence was necessary to preserve Northern Ireland as part of the UK. These groups on both sides are often referred to as paramilitaries.

The March

On January 30, 1972, thousands of marchers assembled for an anti-interment demonstration. Estimates put the crowd, which included many women and children, at 10,000-15,000 people.

In preparation for the crowd and in anticipation of possible riots, authorities dispatched the British Army to set up along the march route.

Protestors intended to march from the predominantly Catholic area known as Bogside to the city center of Derry. But the army set up barricades to re-route the march away from the intended destination.

Most of the marchers altered their route and turned away at the barricades, but several hundred, mostly young people, continued on the original path.

These marchers threw rocks and bottles at the armed military forces. In response, the army used water cannons, CS gas, and rubber bullets.

While this kind of skirmish had almost become commonplace during The Troubles, it quickly turned historically tragic.

At another location in the city, soldiers fired five bullets at marchers injuring two people including one who later died from his wounds.

The OIRA fired a single shot at British soldiers after their initial volley.

Soldiers were given the order to conduct an arrest operation to quell the conflict, but they were not supposed to give chase to any of the participants, and they were supposed to take care to separate violent protesters from peaceful ones.

That didn’t happen.

Instead two armored vehicles entered the predominantly Catholic area of Derry, and as the crowds ran, soldiers got out and started firing.

The march began shortly after 3pm. A little over an hour later, 13 men and boys lay dead - innocent and unarmed marchers shot down by members of the British Army’s Parachute Regiment; a 14th man died later from his wounds. Seventeen others, including two women, were injured. Some were shot in the back as they tried to flee. One victim was shot a second time and killed as he lay injured, others were shot as they tried to help the injured and dying. - Museum of Free Derry

Nearly everyone who had been injured or killed had been struck in the span of fewer than 10 minutes. No British soldiers sustained casualties.

If you’ve read this far, then perhaps you find this kind of research and writing useful. I need your support to keep it up. Will you consider becoming a paid subscriber today?

The Aftermath

Re-writing the history of what happened on what became known as Bloody Sunday happened almost immediately.

In the aftermath of the shootings, British army officials and news outlets claimed that soldiers only began firing after being fired upon.

They said that soldiers only targeted armed protesters who posed a direct threat and that law enforcement had exercised restraint in the face of rioting.

But a few days later a group of seven Derry priests issued a statement in which they repudiated the propaganda being promulgated.

“We accuse the soldiers of shooting indiscriminately into a fleeing crowd, of gloating over casualties, of preventing medical and spiritual aid reaching some of the dying.”

In response to the public outcry and to explain the events of the day, the British Parliament announced an official inquiry led by Lord Chief Justice, Lord Widgery.

The Widgery report, which was concluded after just 17 days of hearings which relied heavily on accounts from soldiers rather than Derry residents, whitewashed the truth of Bloody Sunday and concluded that marchers and not the British Army instigated the violent confrontation and the loss of life.

This report stood as the official record of what happened on Bloody Sunday until 1998 when a new inquiry was ordered due to pressure from justice advocates.

This inquiry resulted in the Saville Report. It came in at over 5,000 pages long and took more than a decade to compile, but it set the record much straighter regarding what happened on Bloody Sunday.

The Saville Report stated, “The immediate responsibility for the deaths and injuries on Bloody Sunday lies with those members of Support Company whose unjustifiable firing was the cause of those deaths and injuries.”

The report also concluded,

“The firing by soldiers of 1 PARA on Bloody Sunday caused the deaths of 13 people and injury to a similar number, none of whom was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury…Bloody Sunday was a tragedy for the bereaved and the wounded, and a catastrophe for the people of Northern Ireland.” - The Saville Report, 2010

In light of the report’s findings, British Prime Minister David Cameron said, “the conclusions of this report are absolutely clear. There is no doubt, there is nothing equivocal, there are no ambiguities. What happened on Bloody Sunday was both unjustified and unjustifiable. It was wrong.”

Lessons from Bloody Sunday

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was influenced by the Black Civil Rights movement in the United States. Their use of direct action nonviolent protest echoes the marches and protests of the 1950s and 1960s to protest racial segregation and voters suppression in the U.S.

But the path of nonviolence is narrow and difficult. It requires incredible self-discipline, training, and commitment. Bloody Sunday meant that violent paramilitary attacks would largely define The Troubles thereafter.

Bloody Sunday solidified the conviction of certain people—both nationalist and unionist—that only violence could bring about their desired goals.

It initiated decades of back-and-forth attacks that resulted in thousands of deaths.

Ultimately, two inquiries and reports had to be issued to find and broadcast the truth of what happened on Bloody Sunday.

The families and victim advocates had to research and protest for more than twenty years to get a new inquiry that actually sought the truth. The facts contained in the report lent some measure of accountability for the bloody actions of soldiers that day.

While the report could not bring back the victims of the violence, it did lay appropriate responsibility on the armed forces and not the marchers. Such truth-telling is a necessary pre-requisite to peace.

The trauma, grief, and violence still mark the country and communities of Northern Ireland. Tension abounds and segregation between Catholics and Protestants is still a common feature of the land.

Blood Sunday should remind the world, and Christians especially, that we are called to be peacemakers in a world bent toward hatred and violence.

I find it astounding how the power of the police and the military is still being leveraged by those who will not even struggle with full disclosure and accountability when that power is used against the innocent. How is it that truth-telling is still optional to those in power? I thank you, Dr Tisby, for being a truth-teller.