Freedom's Eve: The Watch Night Service That Welcomed Emancipation

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass relates his experience of this historic New Year's Eve in 1862

Stories like these—the untold tales of history—are the ones that need to be shared widely. But some people would like to make this history harder to access. If you want this type of content easily accessible, would you partner in this work with me? Become a paid subscriber today.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a moral and spiritual document as much as it was a political and military one.

The announcement of freedom from the president, limited though it was, acknowledged a self-evident but often-denied reality: Black people were fully human and deserved liberty.

For Black Christians, the Proclamation indicated that they embodied the image of God just as much as any person of European descent. It came as a glad tiding that, like the Hebrews delivered from Pharaoh in the book of Exodus, Black Americans would be delivered from the plantation pharaohs and make their way to the promised land of freedom.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, gestures toward the immediate and complete freedom of enslaved Black people had already begun during the first year of the war.

Gestures at Freedom

In August of 1861, Major General John C. Frémont, commander of the Department of the West, declared martial law in Missouri and issued a proclamation that said if a slaveholder was in rebellion to the United States, “their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared free.”

The order was quickly rescinded by President Abraham Lincoln, and Frémont was soon relieved of duty. In December 1861, Lincoln sent an annual address to Congress in the form of a letter that outlined a controversial plan for gradual emancipation and colonization of Black people to other nations.

Then in May 1862, Major General David Hunter, commander of the Department of the South, declared the 900,000 enslaved men, women, and children in his jurisdiction free. Ten days later, Lincoln revoked Hunter’s order.

A month earlier, in April 1862, one year after the Civil War began, Washington, DC, approved the Compensated Emancipation Act, freeing enslaved people in the district and compensating slaveholders up to $300 per freedperson.

Despite the aborted and limited attempts thus far, it was only a matter of time before Lincoln had to take a public and decisive stance on the true issue of the war: slavery or freedom.

By summer 1862, Lincoln was ready to address the most important military and political issue of the Civil War and the Union—emancipation.

His sentiments shifted on the matter mainly because of the exigencies of war and the constant pressure coming from Black people both enslaved and free.

He composed a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation in July, but his Secretary of State, William Seward, advised the president not to issue it immediately. Given the dismal state of the Union’s military exploits at the time, the proclamation would seem like an act of desperation from a failing army and president.

But if Lincoln announced the proclamation after a significant military victory, it would seem like a statement from a military that was on the ascendancy.

Lincoln took this advice and waited until after the Battle of Antietam in September to make the announcement—hardly a decisive victory, but it would have to do.

The Boundaries of the Proclamation

In September 1862, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which indicated that the full proclamation would go into effect on January 1, 1863, if Confederate forces had not yet surrendered.

The proclamation did not “free the slaves.” It only applied to enslaved people in Confederate territory that had not been taken over by the Union. It left slavery in the border states untouched.

It would take the Thirteenth Amendment to legally abolish slavery nationwide.

Nevertheless, the Emancipation Proclamation officially expanded the war from simply restoring the Union to eliminating slavery in the process. It also allowed Black people to formally enlist as Union soldiers.

After the announcement, Lincoln made this statement: “I can only trust in God I have made no mistake. . . . It is now for the country and the world to pass judgment on it.”

Lincoln understood the gravity of the proclamation both for the war effort and for the nation. As he considered his decision and its import, he looked to God for guidance and an eternal perspective on a temporal matter.

Watch Night Service

For Black Christians, the time between the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862 and when it went into effect in January 1863 was one of hope and anxiety.

Would Lincoln follow through? Would there be a last-minute compromise? Would Black people finally be free?

On December 31, 1862, New Year’s Eve, thousands of Black people gathered in churches and other locations for a “Watch Night” service. They counted down the hours until the

Emancipation Proclamation would officially go into effect. They prayed, sang, and read Bible stories about the exodus and God’s judgment on the oppressor.

In Boston, Frederick Douglass gathered with a massive crowd at Tremont Temple, as David Blight relates in his biography of the abolitionist: “Every moment of waiting chilled our hopes. . . . Eight, nine, ten o’clock came and went, and still no word.”

At last a man elbowed his way through the crowd and said that word had come over the telegraph. Black people were free. Jubilee.

The elation was unparalleled. Black people “got into such a state of enthusiasm that almost everything seemed to be witty and appropriate to the occasion.”

In the early morning of January 1, 1863, an aged preacher named Rue led Black people in his church in singing “Blow Ye the Trumpet, Blow” with lyrics that intoned, “Sound the loud timbrel o’er Egypt’s dark sea, Jehovah hath triumphed. His people are free.”

Ever since that night more than 160 years ago, Black people have gathered in houses of worship to celebrate Watch Night or Freedom’s Eve.

They have placed legalized emancipation in the context of a divine struggle between God’s kingdom and the kingdoms of this world, understanding the struggle for liberation as a cosmic conflict that would in time allow them to emerge from slavery to freedom.

Through tireless agitation, decades of abolitionist organizing, and an enduring hope in God’s divine judgment, Black people had participated in bringing about their own freedom. This generation had finally seen the spiritual moaning of millions fulfilled.

The legacy of Watch Night reminds us that the fight for justice is both spiritual and material. It requires both politics and piety. It is both earthly and heavenly in scope.

Just as Black Christians in 1862 held hope and tension, today’s struggles for freedom feature both faith and waiting.

The countdown to emancipation continues—not only in the remembrance of that historic night of the Emancipation Proclamation but also in the ongoing work to dismantle systems of injustice.

Will we honor this legacy and take up the mantle of liberation in our own time?

What are some ways we are still waiting for emancipation? What kind? What actions can we take to hasten the day of justice? Let’s talk about it!

The above was adapted from The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance. Get your copy today.

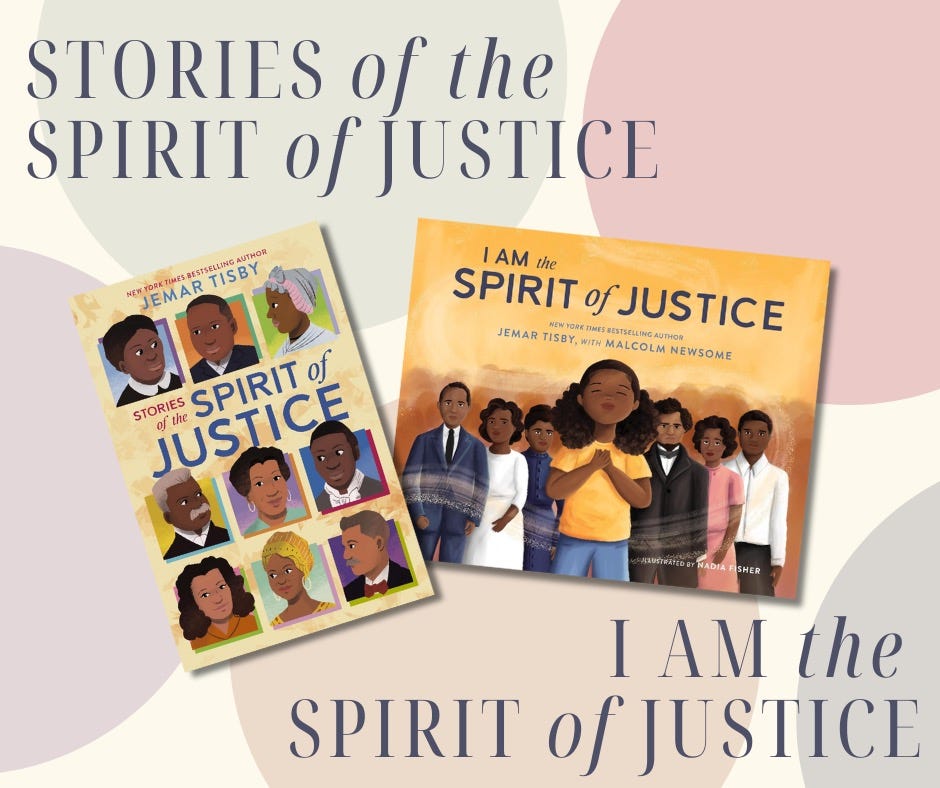

Justice is for all generations. Get I Am the Spirit of Justice (ages 4-7) and Stories of the Spirit of Justice (ages 8-12).

"hasten the day of justice"! Emancipation from white Christian nationalism (wCN). I seek to partner with folks countering wCN, superiority & ways of "whiteness" with acts of love & lifting up people we oppress, including within faith communities. Dr. Tisby's recommendation to learn from the Black Church as the U.S.' Confessing Church helps anchor me. I focus on seeing people & the Scriptures repeatedly drawing our attention to provide justice for marginalized people & to stop oppressing. "Hate evil & love good; establish justice. Let justice roll down like water & righteousness like an "ever-flowing stream." (from Amos 5:15, 24) Let's shine bright!

I loved Costco standing up for DEI despite right wing pressure! Would that more corporate boardrooms and shareholders stand up to the current political climate to be sanctuaries of justice!