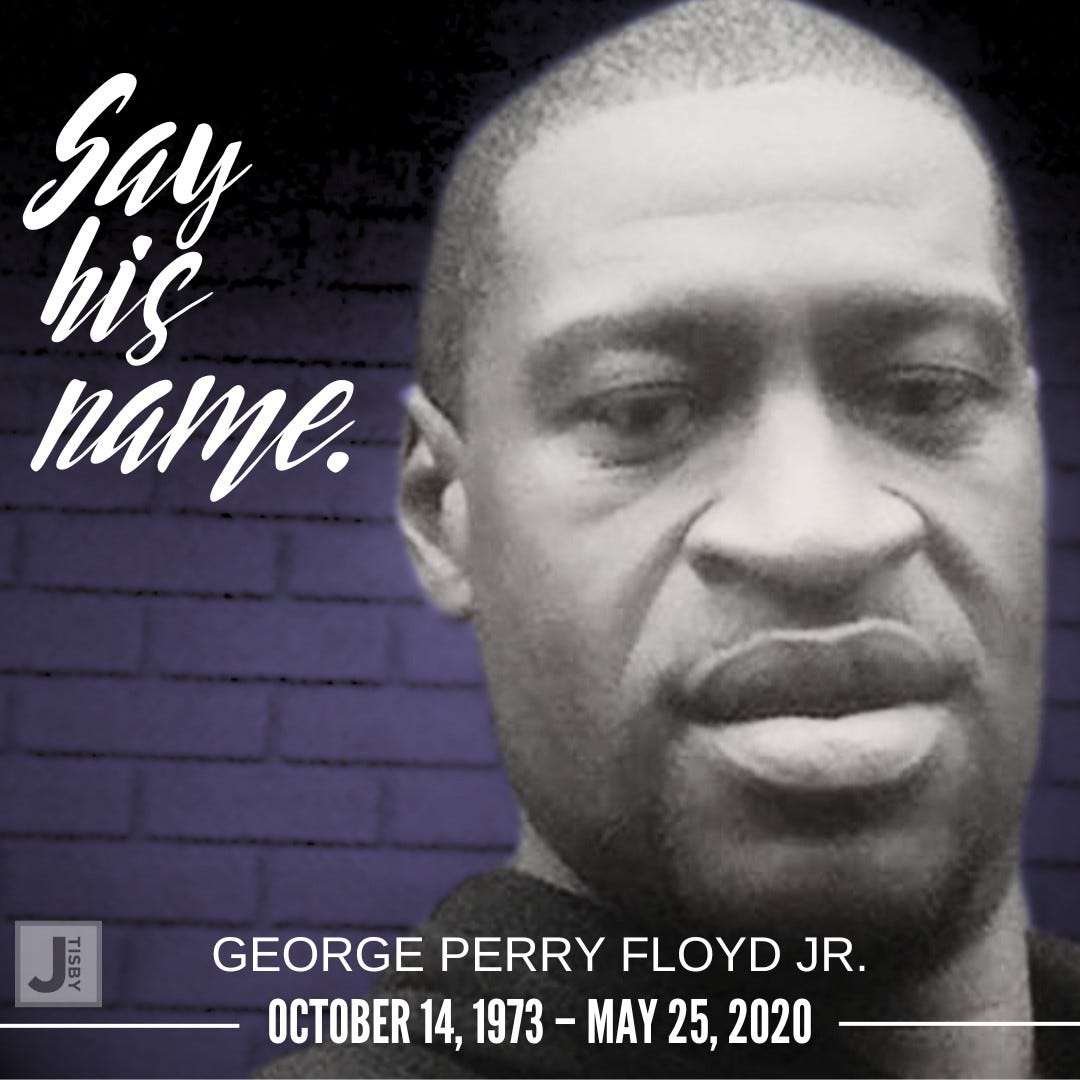

On May 25, 2020 a white police officer kept his knee on the neck of a prone Black man named George Floyd until he died.

The spectacle was captured on cell phone video and broadcast to the world.

The nonchalance of police brutality displayed in the officer’s non-panicked, unhurried torture of an unarmed man who posed him no threat was a visual illustration of the power of white supremacy to end Black life under the color of law.

Floyd’s murder sparked a summer of racial justice uprisings in which millions of people ventured out during the COVID-19 pandemic to protest police violence and the denigration of Black dignity.

Yet Floyd’s murder was just one of several that sparked outrage that year. Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor became hashtags and household names as well.

Yet Black death, particularly by law enforcement and the state continues.

I was recently horrified to learn that in the alarmingly high number of instances of botched executions, Black people face disproportionately higher rates of such errors.

It is not enough that Black people are more likely to receive the death penalty. Even when they do, authorities more often mess it up resulting in hours of agony that can accurately be described as “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Black death is ubiquitous. It seems like community has a story.

I lived in Phillips County, Arkansas where the Elaine Massacre took place in 1919. Then I moved to Louisville, Kentucky, the site of Breonna Taylor’s murder.

There is no safe harbor from the disregard of Black life.

The murder of George Floyd was a rare instance when people around the nation paid attention in a somewhat sustained manner.

Pledges of change occurred in the midst of historic protests.

But the calendar on racial justice quickly turned from December 31, 2020 to January 6, 2021 and a violent insurrection.

In the years since 2020, much of the momentum for racial progress has not only slowed, but reversed.

One executive whose nonprofit foundation saw an unprecedented increase in donations for racial justice before they precipitously declined after 2020 said,

"We're driven to move when an issue becomes acute and when it's the focus," she said. "When it goes back to being normal, we step back into doing our normal thing, which is usually nothing."

Police forces continue to be funded and, in some cases, funds for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) have been diverted to support more “law and order.”

Despite the promises of change, we have yet to truly reckon as a society with the trauma of recorded killings of Black people and the long history of anti-Black violence in this country.

While Black communities themselves weep, lament, and mobilize, the murder continue to happen.

That’s how I know we have yet to fully value Black life. Our lives keep getting discarded.

That Black death has become routine does not mean we don’t feel back when we see it. Most people do not like to witness the spectacle of Black death.

But feeling sympathy does not create systemic change.

We know Black death has become routine not by whether we feel sorry it happens but by the fact it continues to happen.

It’s as if we have come to accept the devaluing of Black life as the cost of doing business in a society full of racial injustice.

The only sufficient evidence that Black death—whether at the hands of law enforcement, environmental racism, poor healthcare, or other causes—is not routine is that more Black people can grow old and live a good, long life.

Until Black death, especially at the hands of law enforcement, becomes a relic of the past instead of routine, we can and must continue to shout, “Black lives matter!”

I am white and I’ve been learning bit by bit about the imbalances and cruelty that are built into our culture and government. But that is an inadequate statement. It’s deeper than that. It’s not culture, it’s not government, it is ALL of us. We allow hierarchies, superiorities, fears, suspicions, differences to build absurd ideas about each other that are not true. We create scenarios of fear that pit us against each other. Whites believe they are entitled and superior. Blacks are forced to work under, around, or through the oppression. To get ahead they must over achieve and be meticulously respectful to build a life.

Black deaths, like George Floyd’s show just how depraved we become. Police serve the white population by imprisoning those we fear, like black people and communities. “Law and Order” are warped words that continue cruelty against blacks, and others that don’t fit within white supremacy’s ideals.

I’ve lived most of my life in the privileged white side. I still live in it. But now I have a window. I have a black son-in-law who has a big, amazing family. My eyes are open, not just to black deaths, but black lives. I get to see first hand, that black families love, struggle, play, grow, learn, and mourn like all families. But they have to work harder, stay invisible to law “enforcement”, be wary of their surroundings, put up with micro aggressions, put up with aggression in order to live here in America.

I can see first hand what we are all missing by living in fear, cruelty and hierarchical BS. I see the missed potential. Oh my, we have cut off our right arm in the name of supremacy and privilege!

My hope is that I clearly speak what I am learning. Black Lives Matter! What will it take for us to learn to value and nurture our humanity in America and around this Earth?

I have to speak out as best I can. I have two grand children who need a better, more humane world. We have to speak, we have to listen, we have to change. As long as it takes.

The death of George Floyd was pivotal in awakening me to pursue antiracism work. As white pastor in a reformed denomination, I was determined that something had to change. But if something was going to change, it had to start with prayer -for apart from the Lord we can do nothing (John 15:5). In October 2020, the Dismantling Racism Prayer Gatherings were started with the support of the Reformed Church in America.

Through this ministry, a sacred zoom space was created for people of all colors to come together to intercede for dismantling racism. It became a place where stories were heard and honored, and the awareness of the work of antiracism increased.

And thank you, Jemar - you have been a mentor/teacher for me.

Thank you for all you do!