Maximalists for Love

How the latest analysis of Christian discourse ignores the Black Christian tradition.

I should have been sleeping, but I wrote this instead. I thought it was important for you to read. If you think it’s helpful (and want to help me get more sleep!), please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In my efforts to promote racial justice I have been labeled with many names. Communist. Marxist. Social Justice Warrior. Woke. Leftist.

The latest label is a new one: Emancipatory Maximalist.

Historian Jay Green of Covenant College used the term in a recent article on “The New Shape of Christian Public Discourse” to describe me and others such as Danté Stewart, Beth Allison Barr, and Kristin Kobes Du Mez.

The Maximalist Position

According to Dr. Green’s description, emancipatory maximalists are “known most widely by their critics as the Woke…But they have largely abandoned the procedural niceties of liberalism in exchange for a hardened vision of identity politics; think Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ advocacy, and radical feminism.”

The emancipatory maximalist is just one quadrant, and the others include: civilizational maximalists, civilizational minimalists, and emancipatory minimalists.

I understand the impulse to create categories. This is often integral to the work of scholars—we have to apply and sometimes create new analytical categories to make sense of the subjects we study.

But categories are clunky. They can easily miss important nuances or be misapplied to place people or ideas in places where they don’t belong.

In this case, my issue concerns how Greene describes the “maximalist” position.

He defines a maximalist as those who, “believe the rules of liberal democracy simply no longer apply.”

According to Greene, maximalists “have gradually come to justify their principled and tactical abandonment of procedural liberalism because their opponents did so first.”

And maximalists have a “whatever it takes” approach to achieving our desired ends.

They aren’t keen on “persuading” their opponents. They wish instead to use coercive power to produce conformity to an unyielding dogma that regulates speech, artistic representation, and institutional policy. Speech that doesn’t conform to these concerns is “harm,” and “Silence is violence.”

I have made my approach toward racial progress clear to the tune of 60,000 words. You can read them in my second book, How to Fight Racism: Courageous Christianity and the Journey Toward Racial Justice.

For the record, I am not “keen on ‘persuading’” stiff-necked people who want to argue that white Christian nationalism is a positive good or those whose hard-hearts refuse to recognize and act against the ongoing hardships caused by racism and white supremacy.

I do not desire conformity. I desire compassion and respect. If those virtues are absent because of racial prejudice, then I may point it out as a way to promote accountability and foster positive racial change.

The Intellectual Segregation of Black Christians

A much bigger issue than mislabeling me and others is the fact that so many attempts to assess the current state of Christianity exhibit an inexcusable ignorance of the Black Christian tradition.

In the context of the United States, Black Christianity arose in direct opposition to white supremacy and racism.

To analyze the current state of Christian discourse without reference to the Black church engages in an intellectual version of ecclesiastical segregation.

Such critiques reflect historic patterns of relegating Black Christians—with all of our faith, thought, and contributions—to the segregated balconies and pews in the Ivory Tower of academia.

The Black Christian tradition in the United States has always engaged in protest—rhetorical, physical, and spiritual—as a matter of existential survival.

Only when white Christians, their institutions, and their discourse are the myopic focus of analysis can one determine that citing the rampant historical examples of racism in the church as a “maximalist” position.

The Prophetic Witness of Black Christians

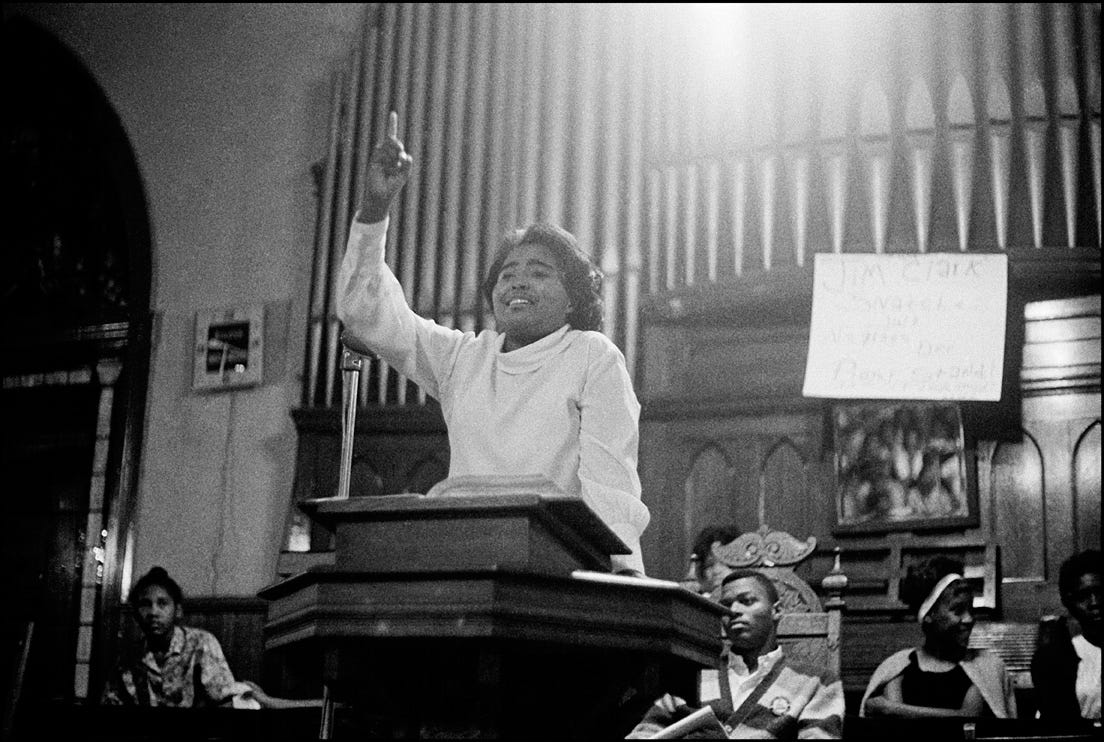

I wonder what Dr. Greene and those who agree with him would think of a Black Christian such as Parthia Hall.

Hall was a theologian, pastor, and powerful speaker. Martin Luther King, Jr. even said he would rather not have to follow her speaking when they were both presenters at an event.

In Hall’s view, racial justice and Jesus’ teachings could not be separated.

Hall called her approach to religion and politics “freedom faith.”

She did not see the realms of the material and the spiritual as separate but integrated. “Faith and freedom were woven together in the fabric of life.”

This vision led to Hall’s work in the Civil Rights movement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and her freedom faith informed her powerful preaching ministry as well.

What might Green think of Fannie Lou Hamer—a staunch Christian who spent most of her life as a sharecropper until she became a national leader in the Civil Rights movement?

Hamer helped form the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a group that attempted to unseat the all-white delegation that Mississippi always sent.

In her view of religion and justice she took seriously Jesus’ call to help the poor. As a a result, she acted to reform voting in Mississippi.

She said, “I could just see myself voting people out of office that I know was wrong and didn’t do nothing to help the poor.”

I could cite many more contemporary examples such as CJ Rhodes at Mt. Helm Baptist Church in Jackson, Mississippi; Kevin Cosby at St. Stephen Church in Louisville; and Ekemini Uwan, a D.C-based public theologian.

In view of the long Black freedom struggle many Black Christians have critiqued their social and political milieu. At the same time, they have generally promoted liberal, multi-racial, inclusive democracy. Indeed the pursuit of Black civil rights has historically led to the greater exercise of democracy for all people.

Hardly the illiberal, maximalist approach by which I and others in the Black Christian tradition have been characterized.

It is not illiberal to demand equality and justice as fellow image bearers of God in the face of intransigent racism and white supremacy.

Too often discussions of Christianity happen with Black Christians (and other Christians of color) as an afterthought or with no consideration at all.

Maximalists for Love

If I am an “emancipatory maximalist” as Green has claimed, then so are millions of Black Christians both past and present.

If I am a maximalist, then I am a maximalist in the same sense as Martin Luther King, Jr. explained that he was an extremist—an extremist for love.

But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love?

To paraphrase King, “Will we be maximalists for hate or for love? Will we be maximalists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice?”

Of the using of labels there will be no end. But do not purport to analyze the “new state of Christian public discourse” without incorporating the indelible and ongoing contributions of Black Christians.

I have read the work of you and your fellow emancipatory maximalists. It seems to me that you are all being denigrated, insulted, dismissed, and called out because you are challenging the empire and it's policies (religious authority, white supremacy, patriarchy, radical exclusion, voter suppression). Jesus challenged Rome, the religious authorities, and their policies so they literally killed him. The religious authorities and political hacks are trying to damn all of you into silence because you are pointing out their violence, hypocrisy, and hatred.

I am wondering if this phenomenon of negative, misrepresentative and often downright slanderous labeling is a “strategy” in the Ephesians 6:11 sense; a strategy of what Charles W. Mills called White ignorance. He wrote that this is an “ignorance that resists…that fights back…an ignorance militant, aggressive, not to be intimidated…an ignorance that is active, dynamic, that refuses to go quietly--…” By God’s grace we have so many resources and teachers available to us to help us learn history more accurately and be discipled out of White supremacy. An often effective way to prevent learning is to misrepresent and denigrate the source of knowledge. That way one can easily dismiss that source as not worth their time and effort without any sense of possibly missing out on something important.