Prathia Hall and the Dream

Without this Black woman preacher MLK might never have said "I have a dream."

This is the first installment in a series on Black women history makers in commemoration of Women’s History Month. Check back every Tuesday to learn about other amazing Black women.

Substantial evidence from oral history suggests that Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I have a dream” line originated with a young Black college student named Prathia Hall.

In 1962, as soon as she finished her studies at Temple University, Hall s the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black freedom struggle. That is how she came in contact with Martin Luther King, Jr.

At a vigil in remembrance of four Black churches that had recently been burned by white supremacists, organizers called on her to offer the opening prayer.

In her invocation she repeated the phrase “I have a dream.”

The nation’s most prominent civil rights leader at the time, Martin Luther King Jr., attended that event and heard Hall’s prayer.

The phrase left an impression on King.

According to Hall’s biographer, Courtney Pace, King looked for Hall after the vigil to ask permission to use the words “I have a dream” in his own speeches—a request she granted without asking for recognition.

King then began incorporating the phrase into his speeches, the most well-known of which occurred at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Pace explains that Hall’s use of a “dream” as a metaphor was an example of her sophisticated theologizing informed by the pursuit of liberation and her Black church roots.

“The repetition of ‘dream’ guided her listeners into reflection on what was and what could be, what had been promised and what had already been fulfilled, what God actually said and what people did in the name of God.”

Who Was Prathia Hall?

Born in Philadelphia on June 29, 1940, Prathia Hall grew up as a preacher’s kid. Her father founded Mt. Sharon Baptist Church in 1938 and remained its pastor until his death in 1960.

The church was a family affair.

In its early days, the congregation met in the Hall home. Prathia and her siblings participated in the church’s ministries including a food pantry and visits to the sick and shut-in.

As was true of many women of the time, Hall’s mother bore many of the responsibilities of raising children, and she left a deep impression of piety and critical thinking on her daughter.

When it came to Hall’s church leadership and preaching, her father was her main influence. He never thought being a woman would diminish her ability to serve God or make a difference in the world. She even carried his handkerchief in her Bible as a reminder of his impact.

As an adult she described her sense of calling in this way:

Well it sounds presumptuous to say you were born with a mission, but I have always had a deep passion for justice. I was raised by my parents in what I believe to be the central dynamic in the African- American religious tradition. That is, an integration of the religious and the political. It is a belief that God intends us to be free, and assists us, and empowers us in the struggle for freedom. So the stories of our history helped me to understand that we were called to be activists in this struggle for justice.

Freedom Faith

In high school and college, Hall participated in the Fellowship Hall, a community dedicated to social justice from a Christian perspective.

Fellowship Hall in Philadelphia hosted Mordecai Johnson, the same meeting Martin Luther King Jr. attended where he first heard about Gandhian nonviolence.

In her piety and activism, Hall practiced what she called “freedom faith”: “the belief that God wants people to be free and equips and empowers those who work for freedom.”

When she joined SNCC, Hall distinguished herself and soon became the second-in-command to leader Charles Sherrod.

She had a hand in training new participants, which was a critical and delicate task since she had to teach white northerners about the strict racial codes of the South and prepare everyone for the very real danger of attempting to disrupt the racial status quo.

She was assigned to Terrell County in southwest Georgia. Because of the acute poverty of its residents and the merciless racial terrorism inflicted upon the Black community by the white population, the county earned the nickname “Terrible Terrell” and “Tombstone Territory.”

One night, when Hall was staying in the home of a local host, the house was shot up by white racial terrorists. Hall sustained minor wounds, but it was a major episode for her.

“That night any and all romantic thoughts about our freedom adventure dissolved as we came face-to-face with the real and present possibility of death.”

Though such violence tested the faith of Hall and her compatriots, they with- stood the trial. Hall remained in Terrell and continued to work for voting rights amid constant danger.

She also blossomed as a preacher.

Many witnesses to her orations were stunned at such maturity and sophisticated theology coming from a young woman.

Even Martin Luther King Jr., with whom she frequently interacted through her work with the Albany movement, said, “Prathia Hall is the one platform speaker I would prefer not to follow.”

Eventually Hall relented to the still, small voice of God in her spirit and pursued ordained ministry. In 1977, she became one of the very first women ordained by her denomination, the American Baptist Church.

She also pastored Mt. Sharon Baptist Church, the church started by her father. In time, she earned a constellation of advanced degrees: an MDiv, a ThM, and a PhD from Princeton Theological Seminary.

In her academic pursuits, Hall became a pioneer of what is now called womanism—theology rooted in the experiences and perspectives of Black women.

She taught in several capacities and ended her career as the Martin Luther King Jr. Chair in Social Ethics at the Boston University School of Theology.

Hall believed that every time a person willingly took the risk of standing up against racism, “that was a religious statement, as profoundly religious as saying a prayer or doing any kind of religious discipline.”

Hall understood what many other people of faith in the movement would come to realize—worship did not begin or end in the hallowed halls of a church sanctuary.

Faith has to be lived.

It has to be exercised in the face of risk, danger, and uncertainty.

What we call the spirit of justice, Prathia Hall called “freedom faith”—God’s work through the community of faith “to set the oppressed free” (Luke 4:18).

Did you know of Prathia Hall? What about her life and witness stands out to you? Comment below.

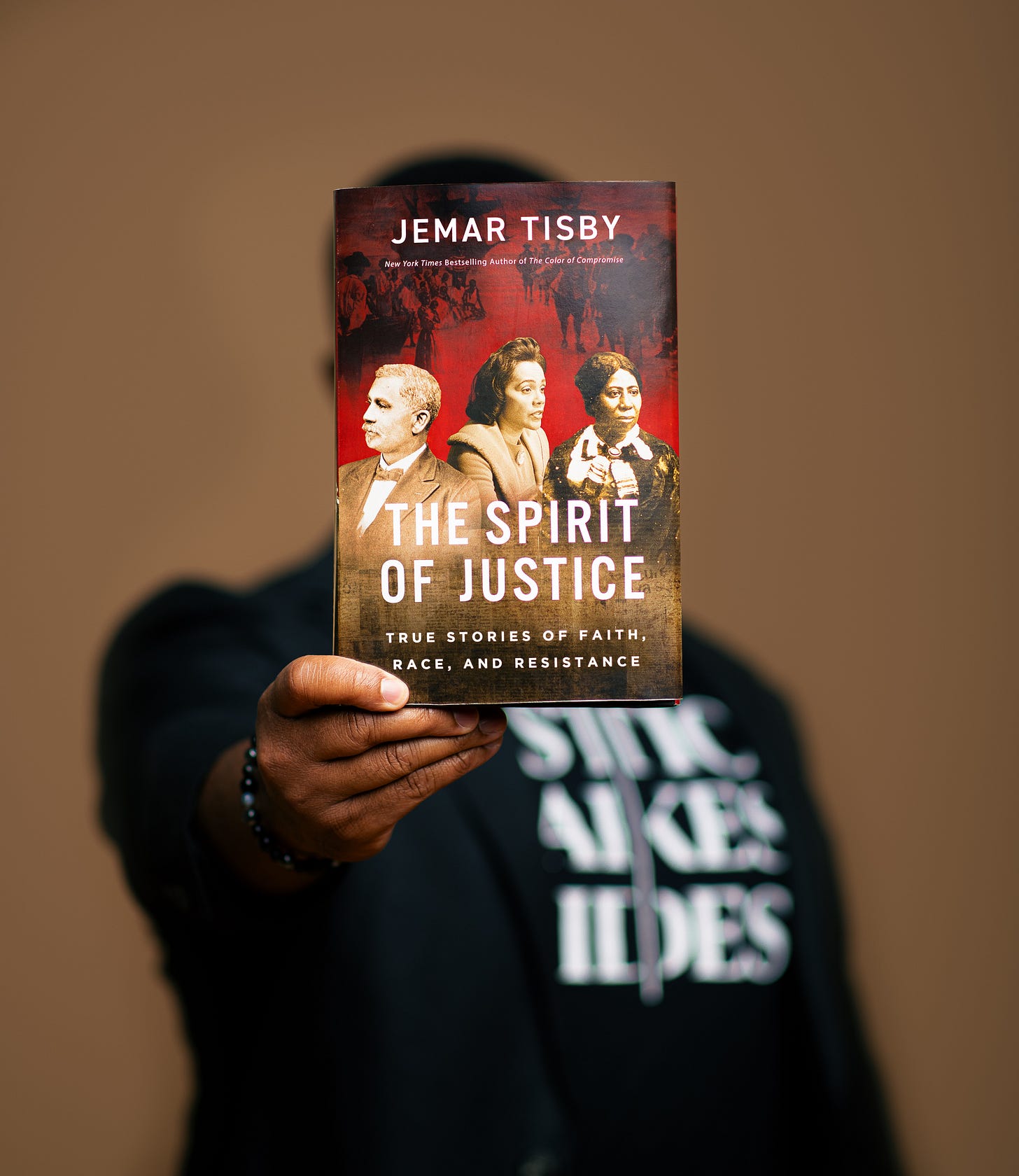

The above has been adapted from my latest book, The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Religion. It will teach you about dozens more Black women history makers.

Get Courtney Pace’s biography of Prathia Hall here: Freedom Faith: The Womanist Vision of Prathia Hall.

What a remarkable story about a woman of God and another "hidden figure" in history!

I'd heard the story about MLK struck by a young woman's usage of "I have a dream," and asking to borrow it, but I'd forgotten who this was. What an inspiring person, Prathia Hall! After reading this, the realization that "politics and religion are integrated" is penetrating further into my depths, making me wonder how I could have ever thought otherwise.