The Article that Changed My Outlook on Policing

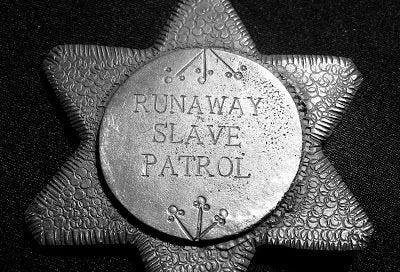

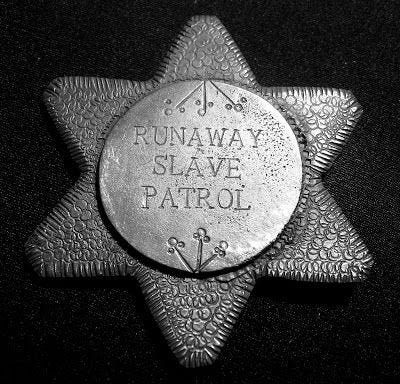

Historian Keri Leigh Merritt shows some of the racist origins of professional policing

This “Footnotes” newsletter is a reader supported publication. If you find articles like these helpful, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber today?

In August 2014, a white police officer killed Black teenager Mike Brown and many in the nation started chanting “Black lives matter!”

I, like many, scrambled to understand what was happening. I wondered how you get a predominantly Black community policed by law enforcement officials who were mostly white.

I began learning about red-lining and racial segregation. I also learned about the racist origins of professional police forces.

As a Black man growing up in the United States, I knew from personal experience how people like me maneuvered under a constant cloud of suspicion and the presumption that we presented a threat to anyone in our path.

I remember a police officer frequently following me and my group of mostly Black and Latino guy friends throughout the arcade on multiple occasions. This always struck me as odd given the venue.

Did he think we were going to slink off with a six-foot tall arcade game under our coats?

I remember getting pulled over on a rural road in Mississippi. The cop followed me for several miles while I assiduously adhered to the speed limit and drove as sedately as I could. Nevertheless, he turned on his siren and pulled me over. He ordered me out of the car, told me to put my hands on the hood and spread my legs while he searched me. The cop let me go without so much as a warning. Apparently, I just looked suspicious.

But until I started learning more about the modern police force, I did not clearly grasp how the much of the entire institution had its origins in racism and white supremacy.

One article set me on the path to a deeper understanding of the problems with professional policing and its links to the continuation of racism and white supremacy after the Civil War.

In 2016, historian Keri Leigh Merritt wrote for the Black Perspectives blog an article entitled, “One Continuous Graveyard: Emancipation and the Birth of the Professional Police Force.”

I stumbled across the article on social media, and what initially gripped me was the horrifying picture of a young Black male lying on his side on the ground and around to a vertical pole. The young boy looks like he’s in his teens or early twenties, and is curled in the fetal position. His hands are tied just above his ankles and the metal pole rises up behind his knees and in front of his elbows so he cannot stretch to his full length.

Who deserves this kind of treatment, even if they are convicted of a crime? How can we do this people who are like us in nearly every way except skin color and circumstance?

Merritt explained how policing and its related practice, incarceration, were largely designed to control Black bodies after the abolition of slavery.

Following emancipation, the number of people arrested in the Deep South rose significantly as the substance and enforcement of certain laws changed considerably. In stark contrast to the antebellum period, the vast majority of those now arrested were black.

Far from embracing emancipation, white leaders created new laws and policies to control and incarcerate recently freed Black people. Merritt goes on to explain,

Historian Steven Hahn rightly concluded that “Vagrancy ordinances, apprenticeship laws, antienticement statutes, stiff licensing fees, heavy taxes, the eradication of common-use rights on unenclosed land, and the multiplication of designated ‘crimes’ against property constructed a distinct status of black subservience and a legal apparatus that denied freedpeople access to economic independence.”

Once Black people were in the carceral system, often because they couldn’t afford to pay the fines for minor violations, they faced a perilous fate.

The convict-lease system arose as a new form of labor exploitation after slavery. Companies or even state agencies would “lease” the work of incarcerated people from prisons. The laborers garnered no wages and white business owners could force them literally to work to death.

One prison bureaucrat bluntly remarked that “if tombstones were erected over the graves of all the convicts who fell either by the bullet of the overseer or his guards during the construction of one of the railroads, it would be one continuous graveyard from one end to the other.”

The forefront of the modern civil rights movement is policing and the criminal legal system. Cell phone videos of Black people being killed by those wearing a badge have thrust the realty of anti-Black police brutality into our consciousness. The anxious encounters with law enforcement that so often and tragically turn deadly remind us that the system was not designed to protect Black bodies but to control them.

If we are going to increase public safety, foster healing among victims, and restoration among perpetrators, then we must understand how modern policing reinforces and perpetuates age-old patterns of racial injustice.

Read the rest of the article HERE.

It seems to be an unsolveable problem -- that the American policing system is so strongly oriented towards controlling Black bodies and Black lives. Individual actions of protest don't seem to move the needle much, and when attention wanes the policing system reverts to its normal philosophies of control and dominance.

But I believe that the problem is solvable through group action. Through education and awareness. Through changes in voting. Through changes in policy. Through changes in corporate interactions with the policing system. Through changes in developing alternate systems that can exist alongside of, or even in place of, the current system of American policing.

I wish there was that magic token that could completely replace the American policing system, top to bottom, with a system that can deal with certain threats to public safety without focusing on Black Americans. That token doesn't exist, and merely wanting something isn't going to do anything to change what is a thoroughly embedded and enmeshed system.

So it takes education and teaching and preaching and conversations and group projects to build the consensus that we can do better than we are doing now, that we can establish a fair, just, and non-toxic system of keeping the peace that doesn't require dominance and violence and death as the only tools to respond to calls for assistance.

I wish it were easier, and I wish there were shortcuts. I just don't see an easier path that the one set before us--to continuously work for justice for the people.

Thanks for the reminder that we simply *must* do better by our siblings.

Thank you Jemar for continuing to bring to your audience things we need to know that were not / are not taught in our American history classes. I am sickened by what I read here as a white person. And working as a volunteer at Rikers Island in NYC, I can testify that the vestiges of this travesty continue on today. The more I learn about our own sordid history I see why the Nazi's thought they could learn from us. Lament upon lament.

And thank you Stephen for your edifying and hopeful comment.