The Speech They Wouldn't Let John Lewis Give during the March on Washington

Organizers said it would be too inflammatory. What do you think?

This article is the first of a three-part series leading up to the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington. If you appreciate this kind of historical context, become a paid subscriber today!

On June 11, 1963 President John F. Kennedy gave a speech on the topic of civil rights. The address came in response to events that had transpired earlier that day.

Alabama Governor, George Wallace, had made a dramatic made-for-tv statement against integration by standing in front of the schoolhouse doors at the University of Alabama. He wanted to prevent two Black students—Vivian Malone and James Hood—from desegregating the university.

While the National Guard and U.S. Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach ensured that Malone and Hood enrolled, the incident highlighted the ongoing resistance to desegregation and Black civil rights. So in his speech that evening, Kennedy vowed to propose legislation to guarantee the civil rights of all people.

The speech and Kennedy’s public commitment to civil rights marked a shift in the Civil Right movement, but many activists were skeptical. One person who had reservations was John Lewis, the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

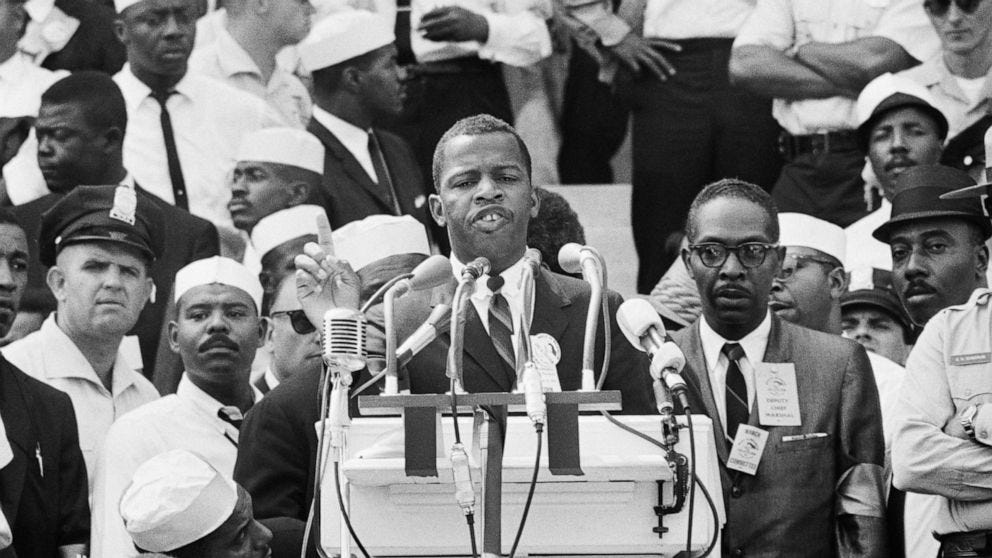

As the leader of one of the most significant civil rights groups of the era and a veteran in the movement, Lewis was selected to give one of the many speeches at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963.

When Lewis submitted his planned remarks to the organizers for a review, they had strong reservations about his words.

Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Burke Marshall, head of the Civil Rights division of the Department of Justice, both read Lewis’ remarks and agreed they could not be delivered as written. Catholic leader, Cardinal Patrick O’Boyle, threatened to withdraw from the March where he was supposed to give the invocation if the speech was not changed.

In spite of the opposition, John Lewis refused to alter his words.

Just moments before the speeches were set to begin during the march, a small group of leaders gathered with John Lewis and his SNCC colleagues to convince him to deliver an edited version. Leaders including Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King, Jr. urged the shift.

In the end, Lewis acquiesced and gave an edited version of the speech. The march and the speakers proceeded without incident and King delivered the day’s most memorable remarks in his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Today, the speech Lewis is most remembered for is not the one he gave at the March on Washington but the one he was not allowed to offer that day.

What follows are some excerpts from the speech and some comments to provide context and interpretation.

Lewis zooms to the heart of the march in his opening sentences. The march was originally conceived as a wake-up call to the nation and politicians about the economic plight of Black Americans—a crisis that had not received sufficient attention amid all the drama of desegregation attempts like the one at the University of Alabama earlier that year.

We march today for jobs and freedom, but we have nothing to be proud of, for hundreds and thousands of our brothers are not here. They have no money for their transportation, for they are receiving starvation wages, or no wages at all.

Then Lewis refers explicitly to President Kennedy’s proposed civil rights legislation. Lewis points out what he views as the deficiencies of the bill and why he cannot offer unreserved approbation.

Lewis points out the failure to address police brutality. In the twenty-first century, the epidemic of anti-Black police brutality launched the Black Lives Matter movement. But even in 1963, no demand for civil rights was complete without addressing the ways law enforcement targeted and terrorized Black communities.

In good conscience, we cannot support wholeheartedly the administration’s civil rights bill, for it is too little and too late. There’s not one thing in the bill that will protect our people from police brutality.

Lewis also points out that the legislation will not actually do much to ensure the voting rights of the nation’s most vulnerable populations. Any bill that could not holistically ensure the right to vote for the people who had historically been excluded from the right was not one he would support.

The voting section of this bill will not help thousands of black citizens who want to vote. It will not help the citizens of Mississippi, of Alabama and Georgia, who are qualified to vote but lack a sixth-grade education. “ONE MAN, ONE VOTE” is the African cry. It is ours, too. It must be ours.

From addressing the deficiencies of the proposed legislation, Lewis moves to impressing upon his hearers the exigencies of the time and why change could not be delayed. The necessity for immediate transformation is a note that Martin Luther King, Jr. would also sound in his “I Have a Dream” speech at the march when he spoke on the “fierce urgency of now.”

The revolution is at hand, and we must free ourselves of the chains of political and economic slavery. The nonviolent revolution is saying, “We will not wait for the courts to act, for we have been waiting for hundreds of years. We will not wait for the President, the Justice Department, nor Congress, but we will take matters into our own hands and create a source of power, outside of any national structure, that could and would assure us a victory.”

To those who have said, “Be patient and wait,” we must say that “patience” is a dirty and nasty word. We cannot be patient, we do not want to be free gradually. We want our freedom, and we want it now.

Even though Black citizens have voted overwhelmingly for the Democratic Party that does not mean they do not have their reservations about the party. Lewis points out the fact that when it came to Black civil rights, neither major political party had delivered.

We cannot depend on any political party, for both the Democrats and the Republicans have betrayed the basic principles of the Declaration of Independence.

Rather than withdrawing from the political process, however, John Lewis eventually ran for office and became Congressman John Lewis representing the state of Georgia for 17 terms. This should be remembered when people become disillusioned with the failure of both Democrats and Republicans.

Lewis knew better than most how many promises had been reneged upon by politicians on both sides of the aisle. Instead of disengaging from the political process, though, he became even more involved and spent his latter years advocating for the changes he insisted upon as an activist during the Civil Rights movement.

As a protegé of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the leader of SNCC, Lewis was fully committed to the path of nonviolent social transformation. But he was militant. He courted confrontation with the forces of racism and injustice. In his speech he made clear his willingness to fight with all the nonviolent methods he could imagine.

In perhaps the most inflammatory part of his speech, Lewis invokes the Union Army’s march through the South as imagery for the progress of justice throughout the land.

We won’t stop now. All of the forces of Eastland, Bamett, Wallace and Thurmond won’t stop this revolution. The time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earth” policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently. We shall fragment the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together in the image of democracy. We will make the action of the past few months look petty. And I say to you, WAKE UP AMERICA!

Both during and after the Civil Rights movement, people have debated words—whether they helped or harmed the cause and whose sensibilities should weighed more heavily.

Whether it was “Black Power,” “Black Lives Matter”, “Defund the Police,” or any number of other phrases, language has the power to build support or erode it. Often it can do both at the same time.

The text of John Lewis’ original speech, which he was not allowed to deliver during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, stands a historical reminder of the power of words and the complex and costly negotiations often required during movements for social change.

Read the full speech HERE.

Watch the edited speech as delivered below…

It's a very real thing to weigh the words you say against what you think the reaction might be, and I can understand the conflicts and the attempts to find the way through the moment.

I have nothing but respect for Lewis, and I also understand the need to be super careful on what is said so that as many opponents as possible of racial equality would be able to listen without being triggered.

Leave to white people that thought the speech would be too much. What were they thinking,? That someone might shoot him?