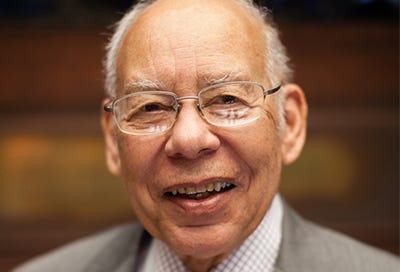

Who is Bill Pannell?

One of the most significant Black evangelicals of the last century just turned 96.

You’re about to read an article about one of the most important topics (Black evangelicalism) and one of the most important men (Bill Pannell) in my life. It is my pleasure to share it with you. Would you share something with me? Consider becoming a paid subscriber today.

You may not know him by name—William E. Pannell (a.k.a. “Bill”)—but if you are interested in racial justice and Christianity, you will want to learn more about him.

Bill Pannell is quite simply one of the most significant figures in Black evangelicalism in the last century.

That is not an exaggeration. Dr. Pannell has literally been alive for most of a century. He turns 96 years old today, June 24.

I first became acquainted with Dr. Pannell while doing research for my dissertation back in 2016. I was writing about another Black evangelical, Tom Skinner, and found that Bill Pannell had worked closely with him at Tom Skinner Associates.

I did some online digging and found to my delight as a historian, that Dr. Pannell was still alive and making “good trouble” in his longtime home of Pasadena, California.

He had no obligation to respond to an email from a random person, but he did.

He was gracious enough to grant me an interview. That was years ago now, and I’ve been so blessed to have many conversations, meals, and laughs with Dr. Bill Pannell.

He has become for me a mentor as well as a true and dear friend.

Dr. Pannell was born in the majority-white town of Sturgis, Michigan in 1929. He came to faith as a junior in high school, and much of his life has been spent in and among white Christians talking about race and justice.

He graduated from Fort Wayne Bible College in Indiana in 1951. He became an evangelist, preacher, and music minister. He spent 10 years as a pastor in Detroit and names the well-respected Black preacher, B.M. Nottage as his mentor and a great influence on his life.

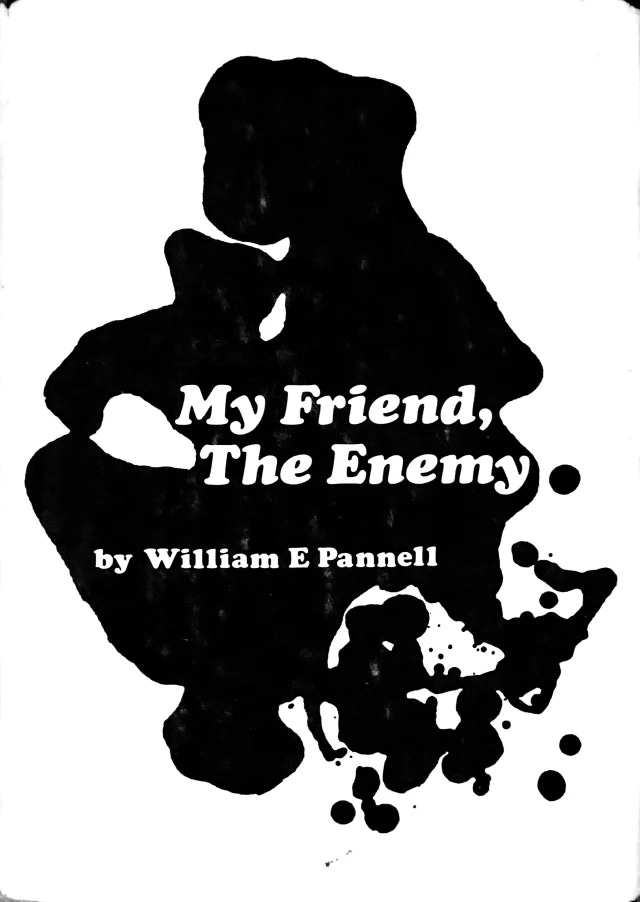

My Friend, the Enemy

Dr. Pannell began ministry in the context of World War II and rising anticommunist sentiments in the U.S., especially from conservative politicians and Christians.

This is also the time when modern white evangelicalism took shape, and Dr. Pannell was a witness to its development.

From 1964 to 1968, he worked for the white evangelical ministry, Youth for Christ.

He became someone who saw from the inside how racism permeated U.S. evangelicalism, and Dr. Pannell spoke out.

In a speech to the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), a mostly white group, Pannell told them in a speech, “I belong to you by background and training…I am a brother. I want to be. But I don’t quite feel at home here.”

In 1968, he wrote the pathbreaking book, My Friend, the Enemy. In it, he leveled a biting and honest critique of white evangelicalism not seen in any book in that era.

He made statements such as

“What right does the oppressor have to demand that his victim be saved from sin. You may be scripturally and evangelistically correct, but you’re ethically wrong. You have the right message, but your timing is off. You have forfeited the right to be heard. I would say, ‘Physician, heal thyself.’”

His comments came not as someone outside of the tradition, but as one deeply embedded in it.

My book, The Color of Compromise, and many other books by Black Christians who decry the racism of white evangelicalism, owe a debt to Bill Pannell and his book.

In 1968, Dr. Pannell joined Tom Skinner Associates (TSA). He was a leader of a small but influential group of Black evangelicals who believed the gospel included both spiritual salvation and justice for the oppressed.

Through TSA, Dr. Pannell and his colleagues preached and evangelized in Black communities and on Black college campuses.

During his time there, Dr. Pannell studied the Black Power movement and its analysis of the racism and social problems in the late 1960s and 1970s.

He examined the Black Power Manifesto and realized its composers had identified three crucial issues related to the plight of Black people in the post-Civil Rights era—identity, community, and power.

The document read, in part:

“Black people in American and in Black nationalist groups across the world have allowed ourselves to become the tool of policies of white supremacy. It is evident that it is in our own interests to develop and propagate a philosophy of Blackness as a social, psychological, political, cultural, and economic directive.”

Filtered through their racial and religious lens, Pannell and Skinner crafted a message that spoke to young Black people who were not sure that Christianity was ever meant for them.

Pannell’s intellectual engagement with Black Power helped inform Tom Skinner’s preaching.

Most people know Tom Skinner from his gripping address at the Urbana student missions conference in 1970. In that presentation, “The U.S. Racial Crisis and World Evangelism,” Skinner offered a historical survey of racism in the US and explained how white evangelicals were often part of supporting racist systems.

Skinner said,

“To a great extent, the evangelical church in America supported the status quo. It supported slavery; it supported segregation; it preached against any attempt of the black man to stand on his own two feet.”

Skinner combined a message of conversion to Christ and the “real revolution” with the necessity to proclaim and work for the physical and social liberation of Black people.

That speech would not have resonated so deeply without the input and insights of Bill Pannell.

Forty Years of Serving the Seminary

In 1971, Bill Pannell became the first Black Trustee of Fuller Theological Seminary. He continued in that role until 1974 when he joined the faculty as assistant professor of evangelism and director of the Black Pastors’ Program. He later served as Professor of Preaching and the Dean of Chapel.

He attained the status of professor emeritus in 2014 after 40 years on the faculty.

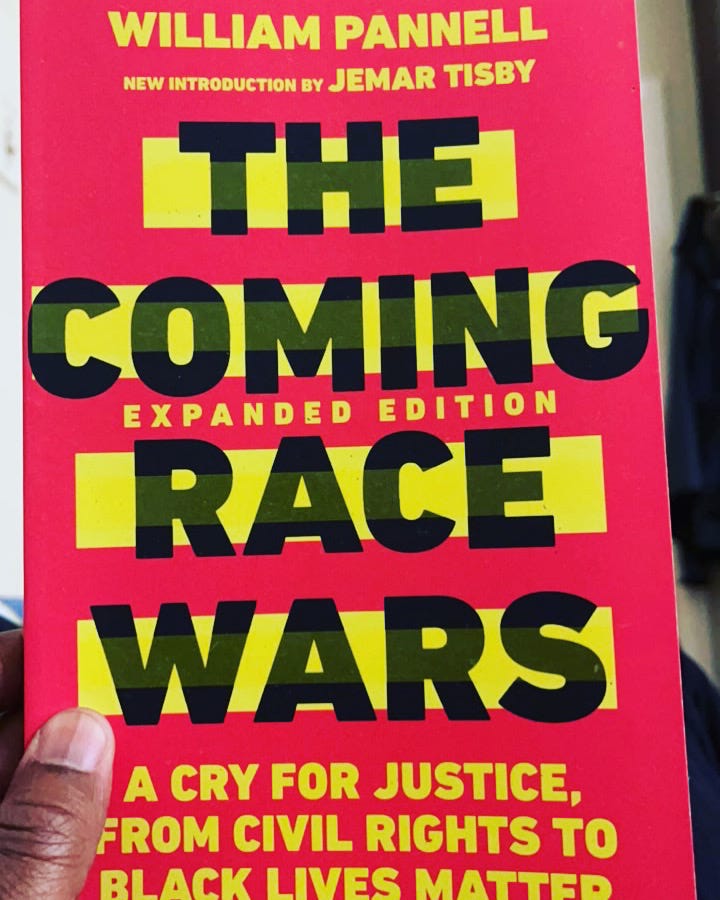

In the wake of the uprisings in Los Angeles, he wrote The Coming Race Wars which was updated 30 years later (It remains one of my greatest professional honors that I wrote the new introduction for it.)

In that book he was prophetic about the rising racial tensions in this country and the imperative for the church to act.

He was adamant that the gospel had something to say about the most pressing issues of justice in our world.

In 2015, Fuller honored him by renaming a center after him—the William E. Pannell Center for Black Church Studies. The Center continues the work of its namesake by providing “by building a body of Black leaders who believe in the power of the church, the community, and the culture.”

You can learn more about Dr. Bill Pannell in an upcoming documentary produced by Fuller Seminary—“The Gospel According to Bill Pannell.”

You’ll also get a preview of this documentary on Sunday, June 30 at 4 pm ET when I conduct a teach-in about Tom Skinner as a memorial on the 30th anniversary of his death.

In that documentary Pannell observed, “Somehow or other in my lifetime, the evangelical movement became more and more American and less and less Christian. They lost their prophetic edge.”

We are in a time when people are looking for Christians to model the life of Christ. They are looking for people who pursue Jesus and justice at the same time.

People today are looking for a gospel that is actually good news. That’s what Dr. Pannell brings. A message of Christ that is compassionate, angered at injustice, and powerful to enact change.

A Real Life Saint

We don’t have many people left who lived through the Civl Rights movement and were on the right side of justice in that era. In Bill Pannell, we have someone who has consistently preached and modeled the values of the Kingdom of God.

For me, Dr. Pannell has been a living example that you can be profoundly dissatisfied with race relations in the church, yet remain a lover of human beings and Christ—tender, warm, and mirthful.

I strive to emulate Bill. He has been around white evangelicals a long time, but he never lost his concern for Black people. He has spoken honestly and truthfully about racism, yet continues in community with all kinds of people. He has run the race and fought the good fight, and in his tenth decade of life dedicates himself to pouring wisdom and encouragement into others.

The Bible says we are “called to be saints”—literally “holy ones” (1 Corinthians 1:2). People set apart from the world, and simultaneously tasked with serving the world.

Yet not many who call themselves Christians could also be called saints. They lack the character, the longevity, the faithfulness, and the love that a true saint must display.

He would never say this of himself, but I will. In the truest sense of the word, Dr. Pannell is a real life saint.

Happy birthday, Bill!

Yes, I know who Bill Pannell is. God bless him and I am so glad he is still with us. I was also at Urbana 70 as a physics graduate student. Tom Skinner‘s sermon is at or near the top of my shortlist of greatest sermons ever, and it was a significant part of my belief at the time that evangelicism could be a positive healing force in America. Unfortunately, I no longer believe that. But I thank Bill Pannell and Tom Skinner for showing me what Christianity could be.

A wonderful tribute to a longtime friend and mentor of those who founded the Chicago Urban Reconciliation Enterprise. I personally love the disarming way Bill would wade into deep conversation and controversial topics with a self-assured grin and friendly demeanor. His impact was and remains significant in my life. Thanks Jemar.