How Mike Brown's Death Changed My Life

A Black teenager I never knew profoundly shaped my understanding of race and myself.

This was an emotional article to write. It took me back to the collective trauma 10 years ago. But I’m committed to making clear the urgency of racial justice. If you appreciate these words, I would appreciate your support. Become a paid subscriber today.

August 9, 2014 marks the 10-year anniversary of the killing of Mike Brown. In the years since then, I’ve realized how his death has changed my life.

In 2014, I was firmly embedded in evangelical and Reformed Christian circles.

I was in seminary at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi. I was an intern at a theologically conservative Presbyterian church. I was in the process of becoming an ordained minister. I was the founder and president of the Reformed African American Network (RAAN). All of my closest friends and colleagues floated about in those circles, too.

This was my life.

My work in those spaces was to talk about racial reconciliation. I believed there was an opportunity for Black people to pull up a seat at the Reformed and evangelical table and assert our presence.

So I offered messages of equality and reconciliation. I talked about Genesis 1:26-28 and how all people were made in God’s image. I extolled the virtue and necessity of intentionally multi-racial churches to offer a visible example of God’s kingdom to come. I preached about Revelation 5:9 and 7:9 and how people from every tribe, tongue, and nation would gather around the throne of Jesus in eternity.

Both praise and pushback resulted from my efforts.

Some people grumbled about all this race stuff being a “distraction” from the pure gospel message. They thought I was being divisive by talking about existing racial divisions. They told me to “let it go” and leave the past in the past.

But many people, including white evangelicals, were hungry for this message of reconciliation.

They wanted to see their churches more diverse. And, I suspect, they wanted to see themselves as “not racist” and assuage some of their white guilt.

Nevertheless, I gained attention through my organizations, podcasts, and writing.

Then came Mike Brown.

On Saturday August 9, 2014 I was teaching a Sunday School class at my church on the mission and vision of the Reformed African American Network. Later that day I led a prayer walk in a neighborhood of Jackson as part of a team discerning whether to plant a church there.

I remember seeing the news about a kid named Mike Brown dribble into my Twitter feed, a trickle turned into a torrent. A human being turned into a hashtag.

#MikeBrown

Over the ensuing weeks and months, Black Lives Matter came to the fore as the new banner under with the next wave of the Black freedom struggle marched.

I began to see more clearly than I ever had the superficial politeness in our churches and society that masqueraded as racial unity.

I learned what a sense of righteous anger felt like as I grew frustrated with the recalcitrance of so many people to make necessary changes to improve race relations in our nation.

The death of this young Black man proved a turning point in my life and ministry.

From Racial Reconciliation to Racial Justice

Mike Brown precipitated the shift from me talking about racial reconciliation to talking about racial justice.

Up to that point, the focus of my efforts was bringing Christians of all races and ethnicities together. By getting in the same rooms and learning about one another we would reduce hate and lower the barriers that kept us apart and at odds.

In this version of racial reconciliation, the problem at the heart of racism was poor relationships. The solution, then, was to foster positive relationships between dissimilar people.

The relational approach to reconciliation is not wrong, it is simply incomplete.

Racism manifests not only interpersonally but institutionally as well. The issue is not only one of poor personal relationships but of poor policies as well.

The evangelical version of racial reconciliation focused on dialogue and changing personal interactions and social networks. There is a place for this, but there is more to do.

Racial justice focuses on changing systems, policies, procedures and institutions. It goes beyond individual actions and mindsets to affect the way we construct our social, political, economic, and ecclesiastical structures.

Mike Brown’s death taught me that all the cups of coffee and pulpit swaps in the world would do nothing to change the history and present reality of anti-Black police brutality.

We needed to go further than making sure officers avoided racial slurs or played basketball with Black kids in the neighborhoods they patrolled.

We needed to reimagine public safety wholesale.

History Has the Receipts

That led to the second way Mike Brown’s death changed my life. I started studying history.

I understood that the brutality of the killing, especially leaving Brown’s body lying on the asphalt for hours in the humid heat of August and in full view of his friends and neighbors, could cause widespread outrage.

But, I’ll be honest, I couldn’t explain why so many Black people felt such a resonance with what happened to someone they didn’t even know in a community far from them.

I understood the feelings. I had endured my own racist and traumatic encounters with the police by then—several times, in fact.

But I didn’t have the frameworks to explain why so many Black people felt such immediate and shared outrage…until I studied history.

When trying to understand the broader implications of Mike Brown’s killing, I came to learn that historians often had the most helpful information.

History has the receipts.

Historians wrote about the longstanding conflict between law enforcement and Black communities.

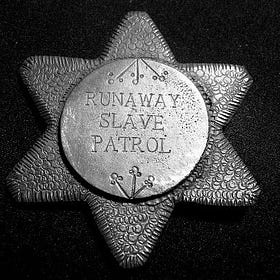

I learned that much of the culture of policing can be traced back to slave patrols, where groups of white men would hunt down Black people to capture, enslave, or kill them.

History demonstrated that significant elements of law enforcement arose as another method of controlling Black bodies after the abolition of slavery.

The Article that Changed My Outlook on Policing

This “Footnotes” newsletter is a reader supported publication. If you find articles like these helpful, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber today?

I came to learn the history of redlining and how you can have a predominantly Black community, like Ferguson, policed by a majority-white police force. And why that dynamic would cause a conflict that ended in Mike Brown lying dead in the street.

Mike Brown made me want to study history.

Just over a year after that fateful day in August 2014, I applied to the PhD program in history at the University of Mississippi with the objective of gaining in-depth knowledge of our nation’s racial past.

Centering the Marginalized

Mike Brown changed my life in another way—no longer would I allow what was comfortable to those most empowered to take precedence over what was most needful to those being harmed.

In the work of racial justice, it is a dramatic and essential paradigm shift to prioritize the needs and concerns of the marginalized instead of coddling the comfortable.

I began to center Black people by focusing more energy on addressing our issues, preventing harm, and seeking healing instead of spending so much time attending to the feelings (fragility) of white people.

In 2017, we changed the name of the Reformed African American Network (RAAN), to The Witness, a Black Christian Collective.

The name change signaled who our core audience was and who we were serving in this ministry.

In 2019, we held our first conference with the theme “Joy and Justice” to encompass the spectrum of the Black Christian experience—we continue to endure racism, so we must work for justice, but in the midst of the struggle we have also found ways to create joy.

In 2021, we initiated the #LeaveLoud campaign—a storytelling project for Black Christians to tell their stories of hurt, harm, and healing as a result of being in and then exiting white Christian spaces.

It was a way to reclaim our voices and our narratives and assert our God-given dignity in a world where our lives hardly seemed to matter.

Thank You, Mike Brown

Ten years after a white police officer killed Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, we continue to struggle for racial justice.

The vigorous demands to oppose racism resulted in equally strenuous efforts to move our nation backward.

The so-called Unite the Right rally, the murder of nine Black churchgoers by a white supremacist at the Emanuel AME church, the continued slayings of unarmed Black people at the hands of law enforcement—all of these have continued since Mike Brown’s death.

And yet, that horrible day became a historical landmark.

A time when millions of people across the country realized anew that racism was still a problem and they had a part to play in fighting against it.

My thoughts, words, and deeds have forever been shaped by the life and death of a Black teenager named Mike Brown.

I did not personally know him, but in lamenting the theft of his life, I have come to know myself more fully and more truly.

Thanks, Mike.

I am an almost 65-year-old White woman who unfortunately remained apathetic after the death of Mike Brown. However, once I learned about the circumstances of the death of Ahmad Aubrey in early May 2020 and then the horrific murder of George Floyd in late May 2020, my apathy was replaced by an insatiable need to understand the history of the injustices we have perpetrated on Black people. At the time, I was a member of a PCA church and thinking they would see that above just about everything else we (the church) should be at the forefront of educating people and showing love to those we have systemically marginalized. Alas, after trying to make headway for almost 3 years, I finally came to realize their white power was way more important than following Jesus and I left the church where I had faithfully worshipped for almost 15 years. I’m now in a more “liberal” Presbyterian church and some of the same struggles exist (it’s so hard for White people to give up even some of their power) but there is space and a handful of people who want to educate others as we learn about these injustices together. What I most regret is that the death of Mike Brown did not move me and it took almost 6 more years. On the other hand, I am thankful that the scales eventually fell from my eyes and I go forward with Jesus with a singular focus on justice for Black people.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts and journey. I never had much of a love of history early on. Seemed in school it was facts, years, dates, key players, etc. As an adult I needed context and that made me start using history for research. Back to your article.

I appreciate your wondering how (Black) people connected so strongly to a "stranger's death". Obiously it was not the person but the setting that connected the historical pattern. As a white person, I am always struck by the intense emotions and connectedness that Black people have to people in the past they also may never have known, but that person or incidence skips generations and time with no gap, and is touching their lives today as if that is their brother/sister/cousin, who lives next door to them today. It's more than empathy: it is identification. I say this because I lack that emotional response to other white people. I still have to find my Mike Brown counterpart.