It Was Always about Slavery

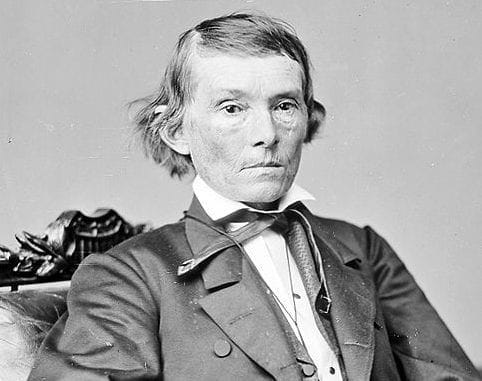

Alexander Stephens' famous "Cornerstone Speech" tells us what the Civil War and the Confederacy were truly about.

A few weeks before the Civil War began, Alexander Stephens, vice president of the hastily constructed government of the Confederate States of America (CSA), delivered a speech.

In what became known as the “Cornerstone Speech”, delivered on March 21, 1861, Stephens pointedly, clearly, and unashamedly touted the pro-slavery stance of the Confederacy and its new constitution.

Among the superior innovations of the Confederate constitution, Stephens listed changes in federal tax policies and shifting the presidency from a four-year to a six-year term with a one-term limit for each Commander-in-Chief.

But Stephens spent the greatest portion of his attention on what he felt was the most important “improvement” of the new Confederacy—slavery

Stephens put it plainly. The foundation of the confederacy—indeed its cornerstone— rested on the existence and preservation of race-based chattel slavery.

The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.

Stephens’ white supremacy was on full display when he explained to his listeners that the only appropriate place for Black people in the Confederate States of America was in a state position of slavery.

Stephens also made clear that slavery was the “immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.” Whatever other reasons may have been appended to secession, its clearest cause was slavery.

He further explained, “[Thomas] Jefferson in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the ‘rock upon which the old Union would split.’ He was right.”

But not only did slavery serve as the reason for separation from the Union, it also served as the reason for the existence of the Confederacy itself.

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.

The United States Constitution and its authors erred, said Stephens, in assuming the “fundamental equality of races.”

Black people could never be equal with white people, according to Stephens, so slavery had to be enshrined as a permanent institution in the Confederacy and its preservation had to be assured in the constitution.

Countering the Myths

White historians, politicians, and civic groups spent decades concocting the myth that the Civil War was fought not mainly over the future of slavery in the United States but simply to preserve the “southern way of life.”1

They created a story with villains—Northern carpetbaggers and Black people who didn’t know their place—who constantly agitated the South, which was only minding its own business, until the gentlemanly white man had to rise up and defend their heritage.

Apologists for the Confederacy also claim that the Civil War was about the principle of “states’ rights”—the duty and privilege of self-governance free from overbearing federal policies.

Under the states’ rights argument, slavery was a matter for individual states to decide. It was not an issue for the federal government or national policy.

These myths about the non-racial, non-slavery causes of the Civil War became enshrined in textbooks, in pop culture through movies like Birth of a Nation and Gone with the Wind, carved in stone with Confederate statues and monuments, and through the repetition of lies until they sounded like truth.

The primary sources, such as Alexander Stephens’ “Cornerstone Speech,” reveal the plot. The Civil War was always about slavery.

Only a willful ignorance or obfuscation of the facts would lead to any other conclusion.

Lies about the causes of the Civil War are why we need history. History has the receipts.

Read the speech HERE.

What else would you like to know about race and/or religion and the Civil War? Maybe I’ll write an article about it! Comment below.

See The Color of Compromise pp. 93-96 for more information about post-Civil War myth-making and the “Lost Cause.”

I’ve been reading that there was a “slave bible” bible that had been edited to take out liberation passages. Certainly many churches supported slavery and the confederacy. Maybe a post on that.

Just last night I was searching for instances of the use of "Slave Power" in free state newspapers in 1858 and it struck me that many of the anti-slavery editors subtly claimed the rhetoric of "state's rights." It's easy to understand. Since the passage of the U.S. Constitution, slave states had worked to ensure to protection of slavery, but by the 1850s, they had become aggressive in advocating for a default Congressional stance on new territories that they would by default be slave territories, that free state citizens had to participate in the return of freedom seekers, and desired a Congressional and Constitutional settlement on the national question of slavery (in its favor, of course). So, they sought to secure slavery as a national concern and compel other states to respect that... they weren't just sitting back asking to be "left alone."

That part where Stephens condemns the founders is as interesting as anything else. It reveals that this is all much, much, more than simple economic advantage for enslavers. Instead, it was a deeply conservative world view that begins with the firm belief that races are not equal, and could not live together as equals, lest violence break out (well, violence to white folks, since white folks already imposed violence on Black people). One did not have to enslave people to believe that to have been a historical fact widely accepted at the time. And it also opens up a view into which we can see that this invocation of an allegedly flawed founding document and the Constitutional order it bequeathed could be so intertwined with the cause of slavery that it's sometimes difficult to tell them apart. (I read these primary sources on a daily basis.) So it makes it difficult for me to insist that these guys woke up in May 1865 and invented from whole cloth the idea that this was all a matter of constitutional issues rather than a defense of slavery, when all of that was exactly the same thing in 1860--no matter where ex-Confederates put the emphasis on a massively complex issue after 1865.

All I'm saying is that, yes, as you say, it WAS always about slavery. And it helps me to understand how slavery found ways to bend political thinking, faith, culture, and social order to it's will, rather than think about it as an either/or proposition.