Even though nearly 17,000 people subscribe to Footnotes, only a small percentage actually become paid subscribers. If you read this article, then you will have knowledge that only a small percentage of people take the time to acquire. Your support makes this information accessible. Will you become a paid subscriber today?

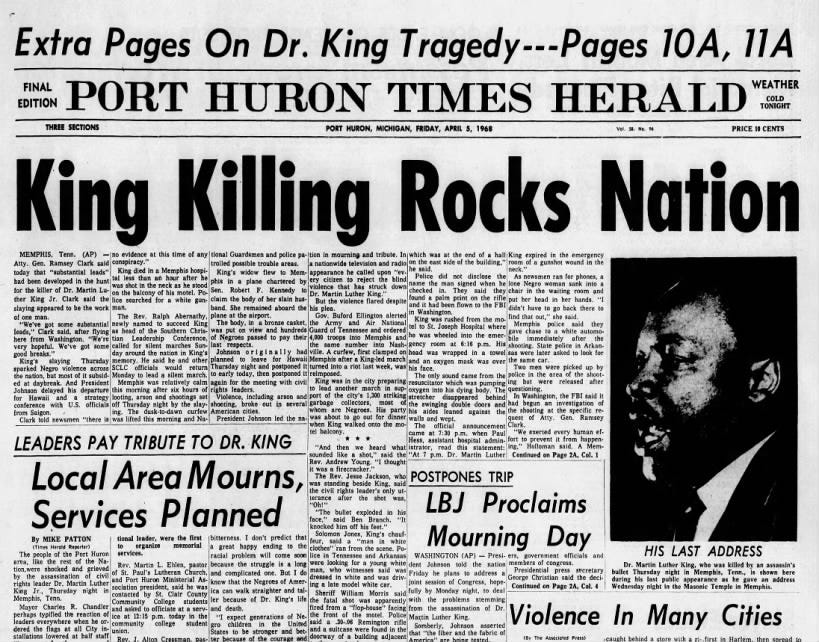

On April 4, 1968, an assassin’s bullet killed Martin Luther King, Jr.

The night before he had given his last public address, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. In it he seemed to prophecy his own fate.

Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!1

When a young Black college student named Dolphus Weary heard the news of King’s murder he was despondent.

Weary was one of the first two Black students at Los Angeles Baptist College (now The Master’s University) when his only other Black classmate ran to him and shared the devastating news.

As soon as news commentators confirmed King’s death, the young Black man “could hear white voices down the hall let out a cheer.”

Reflecting back on this experience, Weary said, “Laughing at Dr. King’s death was just like laughing at me—or at the millions of other blacks for whom King labored.”2

On the anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination, we often discuss the murder itself. This is appropriate and necessary.

And we should also talk about what happened next.

First, it must be noted that even though MLK has become, for most, a national hero today, at the time of his murder he was deeply unpopular with many.

Sociologist Hajar Yazdiha writes in her book The Struggle for the People’s King…

In the final year of his life, Dr. King’s popularity reached its lowest point (75 percent disapproval rating), partly as a result of his public expression of frustration with the political establishment and White moderates’ obstruction of progress.

Still, at the time of King’s murder in the Black community reacted with deep grief. Even if they had never met him in person or attended one of his speech’s or protests, he represented the hope and determination of his people.

Senator Edward W. Brooke, the only Black US Senator at the time said, “The crime is unspeakable. The grief is unbearable…the savage act of his assassin must not be allowed to overshadow the higher vision which Martin Luther King shared with all of us.”3

Famed opera soprano Leontyne Price said, “What Dr. Martin Luther King stood for and was can never be killed with a bullet.

Other Black people responded in anger.

Uprisings occurred in the wake of Kings’ murder in cities such as Washington DC, Chicago, Detroit, Tallahassee, and Memphis to name a few.

Others attempted to honor Rev. King.

On April 8, 1968, just four days after King’s assassination, Representative John Conyers of Detroit first introduced a bill to make King’s birthday a national holiday.

It took millions of signatures on petitions and 15 years before MLK Day became a national holiday.

Two months after King’s murder, his widow, Coretta Scott King, a civil rights leader in her own right, founded the King Center in Atlanta.

The King Center still operates today and is led by Martin and Coretta’s youngest daughter, Bernice King.4

King’s assassination also helped make a long-debated bill become the law of the land.

On April 11, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law.

This act built on the foundation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and included specific nondiscrimination language related to the buying, selling, and renting of housing.

The enactment of the federal Fair Housing Act on April 11, 1968 came only after a long and difficult journey. From 1966-1967, Congress regularly considered the fair housing bill, but failed to garner a strong enough majority for its passage. However, when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson utilized this national tragedy to urge for the bill's speedy Congressional approval. Since the 1966 open housing marches in Chicago, Dr. King's name had been closely associated with the fair housing legislation. President Johnson viewed the Act as a fitting memorial to the man's life work, and wished to have the Act passed prior to Dr. King's funeral in Atlanta.5

Today, the goodwill King’s memory has earned is coming under fire.6

So it is critical to study the life of MLK as carefully as possible, and this includes analyzing what his life and even his death inspired.

Benjamin Mays, president of Morehouse College when King attended and the civil right’s leader’s longtime mentor, delivered the eulogy at his former student’s funeral.

“To be honored by being requested to give the eulogy at the funeral of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is like asking one to eulogize his deceased son, so close and so precious was he to me,” he began.

Mays went on to say,

He drew no distinction between the high and the low. None between the rich and the poor. He believed, especially, that he was sent to champion the cause of the man farthest down. He would probably say, "If death had to come, I am sure there was no greater cause to die for than fighting to get a just wage for garbage collectors." This man was supra-race, supra-nation, supra-denomination, supra-class and supra-culture. He belonged to the world and to mankind. Now he belongs to posterity.

Do you have other memories or stories of what happened after MLK’s assassination? Share them in the comments.

https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkivebeentothemountaintop.htm

From The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism. 150.

The Evening Sun (Baltimore) Fri, Apr 05, 1968. Page 3.

https://thekingcenter.org/

https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/aboutfheo/history

https://www.wired.com/story/charlie-kirk-tpusa-mlk-civil-rights-act/?utm_source=twitter&mbid=social_twitter&utm_social-type=owned&utm_brand=wired&utm_medium=social

I REMEMVBER THAT DAY. I WAS A YOUNG PASTOR IN SEASIDE OREGON AND SPENT HE DAY IN DEEP GRIEF. THEN HELPED ORGANIZE A WORSHIP TIME RESPONSE TO MEMORIALIZE HIM IN OUR SMALL CITY. I STILL REVOLT INSIDE TO THAT DAY AND HIS LEAVING US THE WAY HE DID

I was a white 17 year old high school girl, whose heart and soul was in the civil rights movement. I followed everything that was happening and wished that I could join in on marches or ride the freedom buses. it was a lonely time for me. I didn't know any others in my white spaces who shared my passion. I have many memories of those years. I made up my mind that integration should go both ways and my first apartment was in an all black neighborhood in my town. I also helped with petitions for a MLK national holiday. Thank you for all you do, Jemar Tisby.