Trayvon Martin's Murder and the Death of the Evangelical Racial Reconciliation Movement

Reactions from white evangelicals to Trayvon Martin's murder foreshadowed the end of an interracial era.

If you appreciate this kind of writing that takes race, religion, and justice as serious factors in today’s world, then you can make more of it happen by becoming a paid subscriber.

Beginning around the 1990s, white evangelicals began embracing something called “racial reconciliation.” They made grand public gestures at reaching across the color line to form racially inclusive fellowships, especially between Black and white Christians.

Many Black Christians, especially men, invested themselves in the idea of racial reconciliation as well. They enthusiastically threw themselves into the evangelical racial reconciliation project in hopes of changing not only the church, but possibly even the whole country.

It seemed to be working.

For the next two decades, the number of multiracial churches—where at least 20 percent of the congregation is comprised of people of color–-more than tripled. A study on multiracial congregations found that the percentage of such congregations increased from 6 percent in 1998 to 19 percent in 2019.

Evangelicals began planting churches that stated from the outset that they desired to be a multiracial (yet still largely white-led) congregation. Conference organizers started to make sure that their slate of speakers included at least a couple people of color. Pastors led their churches in “Reconciliation Sundays” and cultivated relationships with Black pastors and their congregations.

The momentum of the evangelical racial reconciliation movement shrouded its weaknesses.1

More committed to grand events than substantive partnerships, more concerned with visible diversity than changing mindsets, more invested in personal relationships than policy transformation, the veneer of unity in the U.S. racial reconciliation movement cracked under the pressure of the murder of a Black teenager named Trayvon Martin in 2012.

What follows is an account of how the evangelical racial reconciliation movement started to crumble in the 2010s. The history is much longer, of course, but Trayvon Martin’s death precipitated the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement which, in turn, exposed the shortcomings of evangelical racial reconciliation efforts in new ways.2

This is one person’s assessment of the impact that the past 10 years of racist events have had on the evangelical racial reconciliation movement. It is not meant to be an academic exploration of people or their actions. It is a brief summary of how the landscape of race has shifted within predominantly white evangelical circles because of changes sparked by the killing of Trayvon Martin.

Ten years after a killer cut short Martin’s life is an appropriate time to see how in many ways, his death also heralded the demise of the modern evangelical racial reconciliation movement.

The Evangelical Racial Reconciliation Project

Most of my Christian life has been spent around white evangelicals and their institutions. As a Black man, then, participating in the movement for racial reconciliation was both by conviction and necessity.

Passages such as Revelation 5:9 anchored my conviction that the heavenly congregation was a multiracial one.

After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb.

I also took Jesus at his word when he taught his followers how to pray.

your kingdom come,

your will be done,

on earth as it is in heaven (Matthew 6:10)

Jesus was telling the disciples that the manifestation of the heavenly kingdom was to be displayed right here and now, not just in eternity. That meant our congregations here on earth should be comprised of the nations as a foretaste of heavenly fellowship.

With the Bible on my side, I trumpeted the message of racial reconciliation in the church.

But my adherence to the message of racial unity was also a matter of necessity. When you’re perpetually in the racial minority the voices and perspectives of the majority constantly clamber over your own. Insisting on inclusion is an imperative.

So I took action.

Waving the Racial Reconciliation Banner

In the summer of 2011 I enrolled at Reformed Theological Seminary (RTS) in Jackson, Mississippi. Within a few months I had founded the African American Leadership Initiative (AALI).

Our goal was to recruit more Black students to the seminary and to equip students of any race for cross-cultural ministry. In a city where 80 percent of residents were Black, we had only a handful of Black students. I wanted to change that.

I also believed that seminary students—our future pastors, missionaries, therapists, and nonprofit leaders—needed to know how to navigate relationships with people from different racial and cultural backgrounds. So me and a small but racially diverse group of students shared meals, watched movies, held discussions, and read articles together.

That same year I also helped create what was then called the Reformed African American Network.3 Our purpose was to pull up a seat at the Reformed and evangelical table in order to make our voices heard and bring up the needs, concerns, and priorities of Black Christians.

Our mission statement said we wanted…

to fuel modern reformation in the African American community and with a multi-ethnic mindset by providing biblically-faithful resources, by connecting Christians who adhere to Reformed doctrines–especially African Americans, and by building theology in community from a Reformed and African American perspective as well as with others from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

AALI and RAAN became the latest programmatic and institutional elements Black Christians and their allies needed to build a dynamic, diverse, and racially inclusive church in the United States.

We hosted events, wrote blog posts, shared on social media and networked with prominent Reformed and evangelical leaders nationwide. We had momentum and enthusiastic support even from white Christians. It seemed like this racial reconciliation thing was about to reach even higher levels.

Then they killed Trayvon Martin.

What Happened that Night

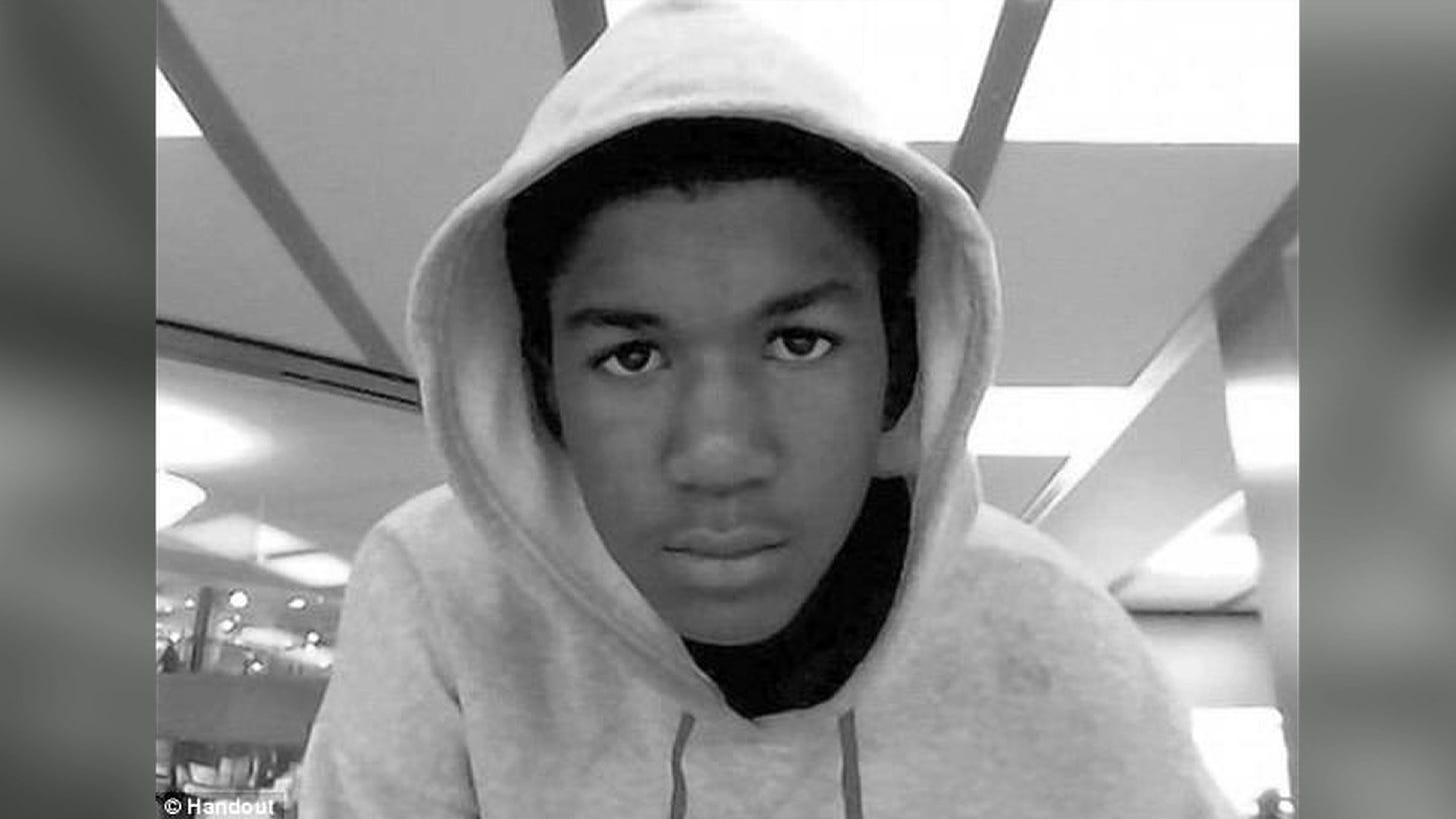

February 26, 2022 marks the 10-year anniversary of the night when teenager, Trayvon Martin, was pursued, shot, and killed by George Zimmerman.

Zimmerman, who is of white and Peruvian descent, acted as a neighborhood watchman in his gated community in Sanford, Florida.

On February 26, 2012, Martin had been walking back to his father’s fiancée’s townhouse, a place he had visited several times before, in a gated community of Sanford, Florida.

He wore a “hoodie” sweatshirt and had Skittles and an iced tea in his hand.

Zimmerman took notice, called the police, but kept tailing Martin. At some point, Martin started running. Zimmerman pursued him, even though the dispatcher told him that was not necessary. Zimmerman responded, “These assholes, they always get away.”

What happened next remains a mystery because only one person remains alive to tell the story. Somehow, Zimmerman and Martin got into a physical altercation. In the ensuing battle, Zimmerman, a licensed gun owner, shot Martin once in the chest. Zimmerman phoned police at 7:09 p.m., and paramedics pronounced Martin dead at 7:30 p.m.

In the span of a few minutes an innocuous walk to the local convenience store for snacks had resulted in a homicide.

Police eventually arrested but then released Zimmerman, who claimed to have acted in self-defense. Florida’s controversial “stand your ground” law permits the use of lethal force if citizens feel threatened in a given situation.

Our Lives Matter

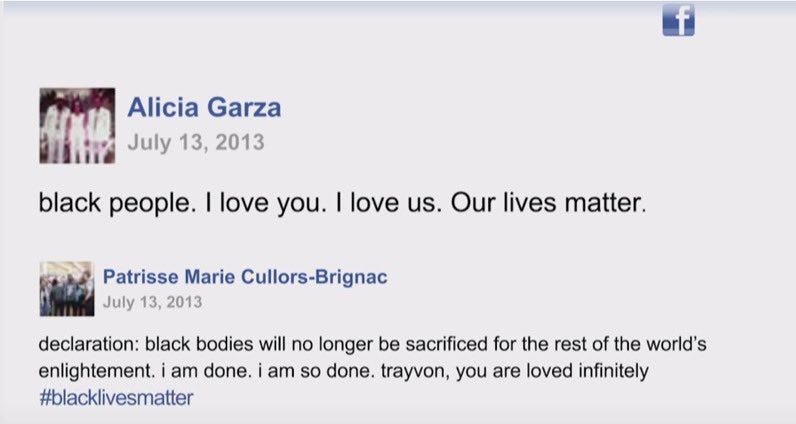

On July 13, 2013, a jury acquitted Zimmerman of all charges.

That same night, Alicia Garza, a black activist and writer in Oakland, California, sat down at her computer to pen what she called “a love note to black people.” In the brief post she wrote, “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.”

Her friend and fellow activist, Patrisse Cullors, responded to the post with the words, “Declaration: black bodies will no longer be sacrificed for the rest of the world’s enlightenment. i am done. i am so done. trayvon, you are loved infinitely. #blacklivesmatter.”

Together with their friend Opal Tometi, these three black women started a hashtag that flowered into a movement that would significantly change the conversation about race and justice in America…and the church.

The Racial Divide over Trayvon Martin

From the moment of Martin’s murder, the rifts between Black and white people nationwide were apparent.

A Pew Research poll found that 49 percent of whites were satisfied with the verdict that acquitted Zimmerman, while just 5 percent of black people surveyed agreed with the trial’s outcome.

When asked whether Trayvon Martin’s death should spur further conversations about race, 28 percent of whites agreed that more discussions needed to take place compared to 78 percent of black people surveyed. Trayvon Martin’s death became a proxy for age-old debates about law enforcement, respectability, and criminal justice.

These differences did not stop at the church doors.

I was in school at RTS and attending a multiracial Reformed and evangelical church throughout the case. I remember hearing about Martin and his death impacted me and my Black Christian friends in a way that many of the white Christians around us failed to understand.

Nearly every Black person realized that Trayvon Martin could have been them or someone they knew. Even the president said it, and drew plenty of backlash for his remarks.

At that point, people like me, those immersed in white Christians spaces and trying to be part of racial reconciliation efforts, sensed in a new way that all our efforts to get different hues in the pews might not be fostering the understanding and change that we hoped.4

The Rise of Social Media

It is important to note that in the early 2010s, social media began demonstrating its power to shape national opinion on current events.

I clearly remember sitting in the admissions office of RTS where I had a job as a student worker in 2012 when I finally started my Twitter account. Facebook was already in full force. Instagram launched in 2010, Snapchat in 2011, and Vine in 2013.

News and opinion about Martin, Zimmerman, and our nation’s racial climate traveled as fast as fingers could tap a keyboard.

At that time, many Black Christians were looking around at white Christian leaders—pastors, seminary professors, authors, and theologians—wondering when or if they would speak up about Martin’s killing or Zimmerman’s acquittal.

One of the most well-known Reformed and evangelical churches in the country, one that had a global reach through its multimedia and digital resources, was located in Sanford, Florida, the exact city where Martin was killed. I scoured their website at the time, but couldn’t find anything related to the tragedy.

Even with the racial divides highlighted by Trayvon Martin’s murder, I and many other Black Christians stayed with white people in their spaces. We believed that now, as the nation once again grappled with racism, we needed to push even hard for racial reconciliation.

Then they killed Mike Brown.

The Black Lives Matter Movement

Most of the nation had never heard of Ferguson, Missouri until suddenly the little community was all over the news.

White officer Darren Wilson killed Mike Brown in a dispute in the street. Wilson was arrested and put on trial.

Once again, an acquittal sparked outrage.

After a highly atypical grand jury procedure, District Attorney Robert P. McCulloch announced that Officer Wilson would not be indicted.

Black people and their allies across the nation responded in outrage. Protestors took to the streets in more than 150 cities. The reality that yet another unarmed black youth had been killed and no one would face legal penalties communicated a message that black lives could be extinguished with impunity.

Black Lives Matter had transitioned from a hashtag to a movement against anti-Black police brutality and a call for renewed efforts to combat racism.

In the wake of Brown’s killing, Christians across the color line weighed in. And they didn’t all have the same perspective.

An article by Voddie Baucham, a Black preacher and theologian, literally crashed the website of a major evangelical blog when he wrote, “Brown reaped what he sowed, and was gunned down in the street…A life of thuggery, however, is NEVER your friend. In the end, it will cost you…sometimes, it costs you everything.”

At that time on the Reformed African American Network page on Facebook, we were asking questions like “What, if anything, should be the response of Reformed churches to the situation in #Ferguson? Share your thoughts!”

One person commented, “I'd love to see the Reformed Church as a whole include themes of social justice in our discussions and proclamations.”

Another wrote, “They should speak out against any injustice and this is no exception. They should address it in a forum where the congregation can have some input.”

And another person said, “Mourning. Sadness. Prayer. Support for the family. Oversight for the [police department].”

As Black Christians with close ties to the white Reformed and evangelical world, however, we were seeing more clearly that racial reconciliation as we practiced it would not be enough to bring about unity and repair.

We started getting pushback. In response to saying “Black Lives Matter” white evangelicals would say “All Lives Matter.” When we called them protests, they called them riots. When we insisted that the church move faster and do more to fight against racism they called us “divisive.”

Mike Brown’s killing highlighted a specific issue, anti-Black police brutality, and demonstrated how anemic evangelical racial reconciliation ideas and efforts were in the face of systemic racism.

Modern evangelical racial reconciliation had flaws in its ideological foundations from the very start.

The Beginnings of the Modern Evangelical Racial Reconciliation Movement

Through the mid-2010s, racial reconciliation was still an oft-used term among both Black and white Christians.5

Of course, Black and white Christians had made attempts to come together in harmony in the same congregations in the past.

In 1944, the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco held its first official worship service. Albert J. Fisk, a white Presbyterian minister and professor, spearheaded the effort to form an interracial church. He invited renowned Black theologian and preacher, Howard Thurman to co-pastor the new congregation.

Thurman was thrilled the prospect. In correspondence with Alfred Fisk about the prospect of starting the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, Thurman wrote, “It seems to me to be the most significant single step that institutional Christianity is taking in the direction of a really new order for America.”

Such attempts were relatively rare and isolated until the early 1990s. In that decade, several high-profile attempts at racial reconciliation occurred.

In 1994, Black and white Pentecostals gathered for a conference in Memphis called “Pentecostal Partners: A Reconciliation Strategy for Twenty-First Century Ministry.” Several presentations on the past, present, and future of racial reconciliation culminated in one white Pentecostal leader spontaneously washing the feet of a Black Pentecostal leader on stage in an act of contrition and repentance.

In 1995, the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination in the United States and one that was founded to preserve the so-called right of white Christians to hold slaves, finally repented of its racist origins. They passed a resolution on racial reconciliation that said, “We lament and repudiate historic acts of evil such as slavery from which we continue to reap a bitter harvest, and we recognize that the racism which yet plagues our culture today is inextricably tied to the past.”

In 1996 the Promise Keepers movement, a ministry to Christian men that holds annual rallies for tens of thousands of people, chose racial reconciliation for its theme. They titled the rally “Break Down the Walls” based on Ephesians 2:14: “For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility.”

At one point in the conference, held at the Georgia Dome, the leader invited the pastors of color to come down to the floor of the arena. They encouraged other pastors to hug them on the way. “We hugged, patted and cheered for 45 minutes. It was wonderfully warm—warmed up the whole conference. There was a lot of crying,” said one white pastor in attendance.

But evangelical racial reconciliation efforts suffered from a fundamental flaw—they were primarily focused on individual behaviors and attitudes.

In this understanding, the forces that separate people of different races and ethnicities come from personal prejudice. An individualistic understanding of reconciliation presents racial separation as the problem. The solution, therefore, is to get people together.

Thus the pulpit swaps, hiring a Black associate pastor or music minister at white churches, and the emphasis on cross-racial friendships

An individualistic view of racial reconciliation tends to overlook or underplay the systemic and institutional factors in racism.

This is why so few white evangelicals had the religious tools to comprehend the priority of repealing racist policies that Black Lives Matter activists called for. It also explains why even saying the words “Black lives matter” in white evangelical circles could get you into an argument about the nature of the gospel and the role of the church in social activism.

Will Black Lives Ever Matter?

So much has happened since Martin’s murder in 2012 and Mike Brown in 2014, it can be difficult to remember the constant onslaught of racist events that forced conversation and attempts at accountability in the nation and the congregation.

A brief timeline of what was happening then may help remind us of how often and how frustrating attempts at racial progress were. What follows is not an exhaustive list, but an illustrative one.

February 2012 - Trayvon Martin killed

July 2013 - #BlackLivesMatter hashtag posted

July 2014 - Eric Garner killed

August 2014 - Mike Brown killed

November 2014 - Tamir Rice killed

April 2015 - Freddie Gray killed

June 2015 - Emanuel Nine Massacre

June 2015 - Trump announces candidacy for Republican presidential nomination

July 2015 - Sandra Bland killed

July 2016 - Philando Castile killed

July 2016 - Alton Sterling killed

April 2017 - Jordan Edwards killed

August 2017 - Unite the Right Rally

Of course, there are so many more people to name, human beings whose lives were cut short because of racial profiling and, oftentimes, brutal policing tactics.

Many of their deaths were caught on cell phone video which only amplified the outrage. When you see another human being, especially one who looks like you, killed on camera it provokes a response.

How could it not?

The string of Black death clearly demonstrated that these circumstances were not “isolated incidents” but part of a long pattern of how this nation has devalued Black life.

As Black people, including Black Christians, advocated for systemic reforms, we saw the support we thought we had from white evangelicals start to evaporate.

I uttered the phrase “Black Lives Matter” and began studying the history of policing and red-lining. I started to understand that merely getting people of different races together on Sunday morning wouldn’t mitigate the existential threat to Black life and flourishing in this country.

If we wanted genuine unity across the racial divide then we needed something more than what evangelicals had made racial reconciliation out to be. We needed racial justice.

From Racial Reconciliation to Racial Justice

Racial justice recognizes that racism never goes away, it adapts. While overtly racist language and laws have rightly been decried, racial inequality remains embedded in laws and policies.

Take Ferguson, for instance.

In the aftermath of Mike Brown’s death, the Department of Justice scrutinized the Ferguson Police Department and found a pattern of anti-Black discrimination. “Data collected by the Ferguson Police Department from 2012 to 2014 shows that African Americans account for 85% of vehicle stops, 90% of citations, and 93% of arrests made by FPD officers, despite comprising only 67% of Ferguson’s population.” And in 14 canine bite incidents in which the suspect’s race is known, in 100 percent of the cases the person bitten was African American.

If racial reconciliation among evangelicals meant wanting Black faces but not Black voices then I couldn’t participate in that movement. If it meant valuing Black presence but not Black perspectives, then I had to leave that kind of “reconciliation” behind.

If evangelical racial reconciliation meant excusing myself from the modern-day Civil Rights movement happening all around us, then reconciliation was a toothless platitude meant to comfort those in power rather than promote the safety and flourishing of the marginalized.

The Breaking of the Evangelical Racial Reconciliation Movement

Anti-Black police brutality is not the only reason the evangelical racial reconciliation movement has suffered in recent years. In the middle of a barrage of racist events, Republicans nominated Donald J. Trump for the presidency and to the surprise of many, perhaps even himself, Trump won.

In a 2018 interview in the New York Times, sociologist Michael Emerson said, “The election itself was the single most harmful event to the whole movement of reconciliation in at least the past 30 years,” he said. “It’s about to completely break apart.”

He was right.

Black Christians like me were already tired. Our voices were worn out crying “Black lives matter!” We found our own breathing shallow as we heard Eric Garner gasp, “I can’t breathe.” Our souls were wearied walking into white evangelical spaces with people who we thought were our spiritual siblings only to hear that our concerns were overblown or part of some Marxist mentality.

Then 81 percent of white evangelicals who voted pulled the lever for Trump.

In the aftermath of the election I recorded a podcast with my reflections in it I said I did not feel “safe” worshiping in my white evangelical congregation that Sunday.

My concern was not for my physical safety but for my emotional and spiritual safety.

I had prayed, sung, eaten, and shared life with white evangelicals. I thought they knew me. I thought I knew them. I thought my concerns mattered. And they did, right up until they entered the voting booth.

I felt betrayed.

Republicans, many of whom identified as white evangelicals, rallied around Trump and his brand of politics even as his rhetoric and actions as president caused chaos and undermined democratic processes and institutions.6

The issue spilled out beyond Trump as an individual and now persists in Trumpism as an ideology. This has affected the ability of Black Christians to remain even in multiracial Christian spaces.

John Onwuchekwa, a Black pastor in Atlanta who very publicly left the SBC in 2020, put it this way.

Although the SBC represents a diverse array of churches across the political spectrum, the denomination conducts itself in a manner that is extremely partisan. (i.e. Influential churches vocal about pulling funding from the SBC when Russell Moore spoke out against basic human decency issues regarding President Trump in 2016; Pence’s invitation and subsequent address at the SBC in one of the most polarizing political cycles of my lifetime; Al Mohler, the President of the largest SBC Seminary and apparent incumbent President of the SBC, using his public platform at T4G to endorse President Trump and reaffirm his personal lifelong allegiance to the Republican Party…and the list goes on and on).

The statistical data bear out this pastor’s assertions.

The percentage of Black attendees at multiracial churches has declined from 27 percent in 2012 to 21 percent in 2019, suggesting that the political and social climate around elections and continued racial unrest may affect a Black person’s decision to remain in a multiracial congregation.

CRT Hysteria - The Latest Blow to the Evangelical Racial Reconciliation Movement

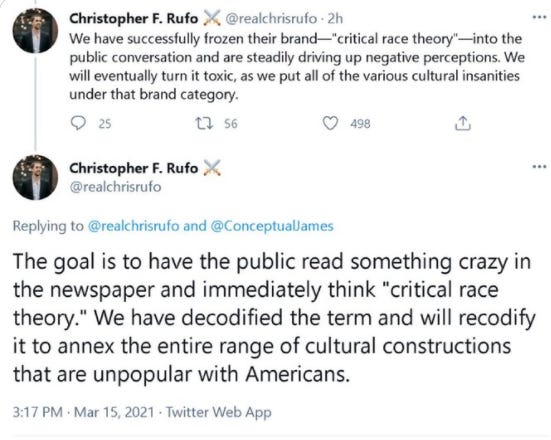

Critical Race Theory has become the latest blow to the evangelical racial reconciliation movement.

Far-right conservative operative, Christopher Rufo laid out the strategy in public in March 2021.

Events within the largest Protestant denomination in the United States back up Rufo’s confident assertion.

In November 2020, the presidents of the Southern Baptist Convention’s six denominational seminaries unanimously passed a resolution declaring “affirmation of Critical Race Theory, Intersectionality and any version of Critical Theory is incompatible with the Baptist Faith & Message.”

The American Bar Association explains that Critical Race Theory (CRT) is “a practice of interrogating the role of race and racism in society that emerged in the legal academy and spread to other fields of scholarship.”

According to a legislative tracker, “So far, at least 36 states have adopted or introduced laws or policies that restrict teaching about race and racism. With 2022 state legislative sessions underway, new legislation is in the pipeline.”

The manufactured hysteria over CRT has caused yet another rift in evangelical racial reconciliation endeavors.

In response to the SBC seminary president statement about CRT, several Black pastors and churches publicly left the denomination.

A Black pastor, Seth Martin, who lives two blocks from where George Floyd was murdered said, “For this to be where they plant a flag this year? It was like, let’s create a problem where there wasn’t.”

Another Black pastor, Joel Bowman of Louisville, left the SBC saying, “I can’t sit by and continue to support or even loosely affiliate with an entity that is pitching its tent with white supremacy.”

Recently, I came under attack yet again for delivering a chapel message at a conservative Christian college that “some students felt was thinly disguised critical race theory garnished with Bible verses.”

What’s Next for Evangelical Racial Reconciliation?

Is the evangelical racial reconciliation movement dead?

I find narratives of declension tend to overstate their claims. I do, however, think the evidence is ample to argue that the evangelical racial reconciliation movement has been severely hampered by white evangelical responses to racist events over the past 10 years.7

When compared to the momentum of racial reconciliation before Trayvon Martin’s murder in 2012 and what is happening in 2022, I find far less enthusiasm from Black Christians for entering into predominantly white evangelical spaces.

Most of the Black Christians I’ve encountered who are still in white evangelical churches, schools, and nonprofits are asking “How long can I stay?” not pondering how to bring even more Black people into a potentially traumatizing situation.

What the past decade has demonstrated is that evangelical attempts at racial reconciliation did not address the deep political and social differences between Black and white Christians.

A move to start more multiracial churches and to offer sporadic representation in leadership has not resulted in widespread unity across racial lines in evangelical spaces.

These efforts have not been entirely negative. Genuine friendships, healthy congregations, and deeper knowledge of Christ’s plan for a diverse global faith have been the byproducts of evangelical racial reconciliation.

In spite of some progress, Black Christians are insisting on truth-telling, justice, and repair as the necessary preconditions to racial reconciliation.

So many of the revelations about the evangelical racial reconciliation movement can be traced back to that fateful night in 2012 when Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black male, was gunned down and no one was held accountable.

Large segments of white evangelical lay people and leaders have made protests against police brutality, the accurate telling of racial history, the reality of systemic racism, Critical Race Theory, and the people who vocally advocate for racial justice into enemies. They desire unity without taking action on the ongoing and systemic nature of racism.

So long as white evangelicals want racial reconciliation without racial justice, they will have to cultivate their belief in miracles—the evangelical racial reconciliation movement will need one to survive.

Some prefer the term racial “conciliation” rather than “reconciliation.” They argue that there has never been a state of harmony between the races so there can be no “re-” conciliation.

Much more can and should be said about the evangelical racial reconciliation movement. This is not an academic treatment of the topic, but an outline of how events in the past decade, beginning with the murder of Trayvon Martin helped shaped the current contours of race in evangelical spaces.

Reformed theology refers to a branch of Christian tradition stemming from the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It emphasizes theological precision and has Calvinistic elements, although it is a diverse tradition with many internal differences. For more see HERE.

White evangelical recalcitrance on matters of racism was not completely unknown to Black Christians. This is why the Black church exists. After the Civil Rights movement, however, there was a hope on the part of Black Christians that widespread and genuine racial unity could be pursued in a new way.

Of course people, including Black Christians, still use the term “racial reconciliation.” Notably LaTasha Brown, founder of the “Be the Bridge” initiative. Her explanation of racial reconciliation includes the call for justice. See her BOOK.

For more on evangelical support for Trump see Jesus and John Wayne by Kristin Du Mez.

I have shared tens of thousands of words about evangelical racial reconciliation. Please visit my website jemartisby.com and reference my books: The Color of Compromise, How to Fight Racism, and How to Fight Racism Young Readers Edition.

"Most of the Black Christians I’ve encountered who are still in white evangelical churches, schools, and nonprofits are asking “How long can I stay?” not pondering how to bring even more Black people into a potentially traumatizing situation."

How did you get access to my dm's??? Haha

I think my ministers believe stuff is finally blowing over. Instead there's a contingent of folks I talk to and each week we have to re-decide to stay

Thank you for this. As a white male who somehow was involved w/ early Black Lives Matter actions in Chicago, and was carried by them into a far greater awareness of my own failures and needs as a Christian and a human, I left Evangelicalism completely as the 2016 election cycle heated up. Your words on that supersaturate moment are profound and - from where I exist - wholly appropriate. That election was a psychological blow to the solar plexus. White Evangelicalism, where I had always thought I had a stake, turned my world and my faith upside down.